Rado has always been regarded as an avant-garde brand. Its watches rank among the few that are recognised at a glance. A member of the Swatch Group, Rado pioneered using and processing materials not typically seen in watch construction. Its best-known watches are its high-tech ceramic models, which first became available in the 1980s. But even before then, Rado was making watches from other hard substances such as tungsten carbide. This compound was first synthesised in 1914 and borders on a ceramic material but is classified as a hard metal.

Rado began in 1917 as the Schlup & Co. watch factory, although at first, the company didn’t produce any watches of its own. Rado Watch Co. Ltd. was founded as a subsidiary 20 years later. Both companies were headquartered in the same building in Lengnau, Switzerland. The first wristwatch to bear the Rado name, the Rado Golden Horse, was marketed in 1957. The watch had a movement from Adolph Schild and a watertight case. It was regarded as robust and reliable. The “golden horse” that gave this watch its name was actually a seahorse, or rather, a pair of seahorses, that appear on the dial as appliqués facing each other. Another distinctive feature made its debut in 1958: a miniature rotatable anchor below the 12 o’clock index and above the “Rado” name, where it not only served as the brand’s logo, but also was the first service-interval display on a mechanical wristwatch. When the anchor no longer obeyed gravity but remained stationery, it was time to service the movement. However, this display wasn’t particularly accurate, and it is often made even less precise nowadays, when most watch collectors and tinkerers mistakenly add a drop of lubricant. In these early years, large numbers of Rado watches were sold in Asian and Arabian countries.

Many of these timepieces are either still in use or available on second-hand watch markets today. Unfortunately, these watches are typically in poor condition due to high ambient humidity and their wearers’ perspiring wrists. Rusty components, corroded cases and tarnished dials are the unwelcome consequences. Therefore, attempts are often made to restore these watches. Newly printed and lacquered dials, along with mixed and matched individual components, make these watches eye-catching misleaders with little real value. One of these watches can cost between `3200 and `6410, assuming that its movement still functions. Well-preserved models with all of their original components are hard to find and usually cost between `12,800 and `32,000.

Rado’s story continues with the debut of the DiaStar 1 in 1962. With a tungsten carbide case and a sapphire crystal above its dial, this watch is almost as hard as a diamond. Its rounded case and wide bezel protect it against the environment. Developing it was very challenging because the new material required new machines and tools to produce it.

At the same time and thereafter, other Rado models catered to the fashion trends of the 1960s. These include the Rado Manhattan, a rectangular

stainless-steel watch with the angular charm of New York’s best-known borough. This model is another that can seldom be found in very good condition. Prices usually range between `9,000 and `41,000. Even rarer is the Rado Cape Horn, which was styled as a “TV screen” watch of the 1960s.

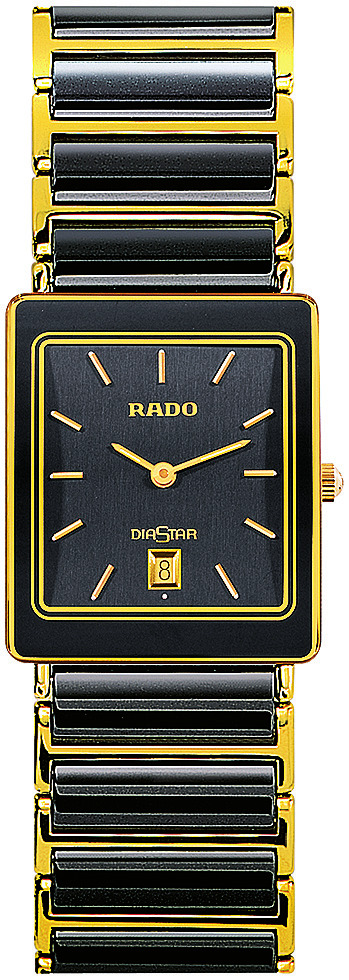

In the 1980s, Rado unveiled a watch that has been nearly synonymous with the brand’s name: the Rado Integral. The brand invested many years of work in its planning, design and engineering. The Integral’s design unites minimalism and high technology. Its case and bracelet are made from bicolor high-tech ceramic. The material starts as a powder that’s pressed into shape at an extremely high temperature. The searing heat melts the powder, which later hardens to produce a homogeneous surface. However, this process also causes the material to shrink, and the shrinkage varies depending on the thickness of the part. This kept Rado’s engineers busy before they finally figured out how to fabricate parts that satisfy the extremely narrow acceptable tolerances required. Sapphire was chosen for the crystal, and a reflective metal coating on the underside hides the glue that affixes the crystal to the ceramic case. Fragments of sapphire can sometimes break away along the edges of the crystal, but Rado can still replace crystals on these models.

With the Integral, Rado found the design that continues to epitomise the brand’s watches to this day. Watches that were made during the first years of the Integral’s production still look good today: their design has long been acknowledged as timeless. Quartz movements make these watches inexpensive to maintain. And relatively low prices put smiles on aficionados’ faces. Second-hand ceramic watches usually start around `32,000, depending on the model and size. Price tags up to `1.34 lakh (approx.) may dangle from more recent versions.

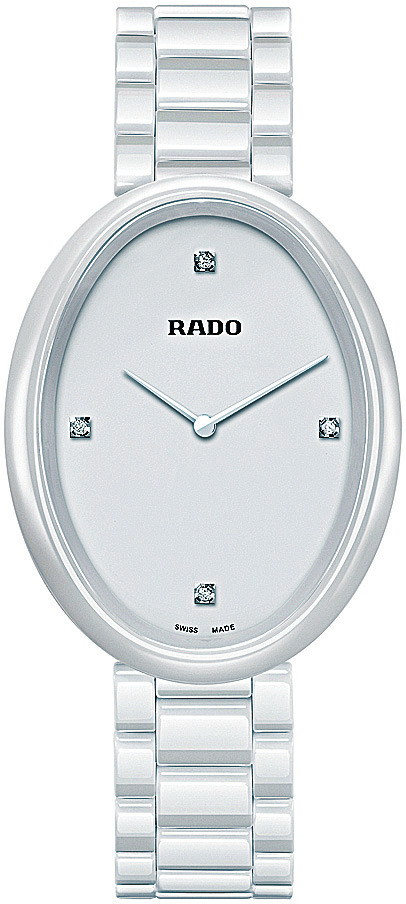

White ceramic watches, which were first delivered in 1991, commanded higher prices. The round-cased Rado Coupole made “white” the new trend in ceramic watches. Rado’s other milestone watches are the Sintra, the Ceramica and the V10K. Their common denominator: all are manufactured using a new, innovative method. For eample, the Ceramica debuted in 1998 and features high-tech plasma ceramic that has a warm metallic shimmer without mixing any metal into the ceramic blend. And the V10K, introduced in 2002, has a unique scratch resistance that comes from coating it with a layer of artificial nano-crystalline diamond, which gives its surface a hardness of 10,000 Vickers and made it the world’s hardest wristwatch.

Rado debuted the D-Star in 2011, almost 50 years after the premiere of the DiaStar 1. The new model revived the design of the 1960s, with a wide bezel and an oval case. The case is crafted from Ceramos, a composite material made from titanium carbide and injected ceramic. This next step in the development of ceramic materials made it possible to create new and even more interesting designs. One example: the extremely slim Rado True Thinline, which also debuted on the market in 2011. This ultra-flat quartz watch is less than 5 mm thick and has a monobloc case. In the meantime, cases and bracelets are made from injection-molded material, which simplifies and adds greater precision to the manufacturing process.

The acme of minimalism came in 2013: the Esenza Ceramic Touch is the first ceramic wristwatch with integrated touch technology. Four sensors are embedded in the monobloc case so the wearer can set the time simply by tapping or swiping with a fingertip. This watch unites Rado’s classic design and modern technology.

After black, white and various metallic tones, 2015 saw the debut of a new color in Rado’s design spectrum: brown. This unconventional hue added a special note to the HyperChrome Brown Ceramic.

In 2016, Rado returned to the design of the ’60s and built a stylish bridge to the Cape Horn collection from that bygone decade with the HyperChrome 1616. ETA’s self-winding Calibre C07.062 is ensconced inside a boldly styled angular case that has a diameter of 46 mm. The case is available in black ceramic or metallic-colored titanium. The latter is a specially processed alloy of this lightweight metal, which boasts a surface hardness of 1,000 Vickers. The dial has all of the features that made Rado a pioneer in the ’60s: along with a bicolor day/night display, connoisseurs will also rediscover the rotatable anchor that’s a sign of the mechanical inner mechanism as well as the brand’s logo. The allusion to the brand’s grand past and the new watch’s instant recognisability prove what collectors have long known: Rado offers classics that are usually ahead of their time.