Kurt Klaus is an incredible storyteller. Over the last five decades, he has lived through the best and worse of the Swiss watch industry, and has created history with some ingenious horological solutions. Of all his legendary stories about watchmaking, the sweetest one is his longstanding relationship with the Schaffhausen-based IWC. It all started as a submission to love. Not for watch- making, but for his then-girlfriend and now-wife, who insisted on moving out of Grenchen - where he was serving under Eterna - to somewhere close to home in St. Gallen . It was then that Klaus shifted to Schaffhausen and was selected by IWC legend Albert Pellaton himself to join the manufacture at the age of 22. What happened in the years that followed made history – among other things, Klaus developed the Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar Chronograph.

Until the late 1970s, IWC had never attempted a complication. It made simple timepieces with the hours, minutes, seconds, and date functions. The Schaffhausen-based watch brand wanted to create, what Klaus later defined as, “the new generation of perpetual calendars”. The town of

Schaffhausen was not new to the concept of perpetual calendars at the time. It was home to the world-famous Joachim Habrecht astronomical clock, which displayed days, moon phase, positions of the sun in accordance with the zodiac, seasons, equinoxes, lunar nodes, and eclipses. Created in 1564, the historical clock still looks out over the town from the Fronwag Tower.

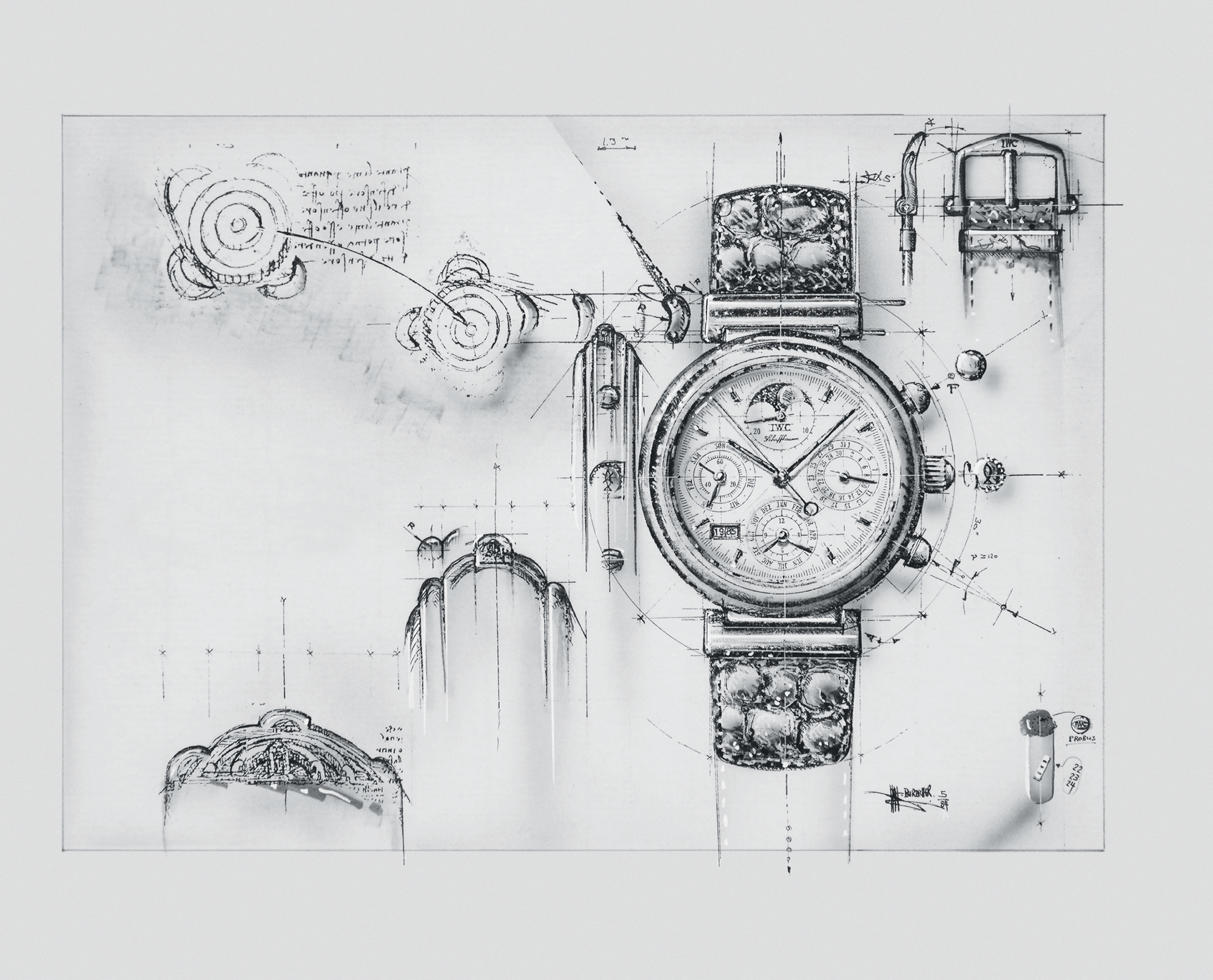

Considering the immense history of such complications, the question arose whether all this could be miniaturised to fit the scale of a wristwatch. Klaus answered that question in 1985 with the Da Vinci Perpetual Chronograph, in which all the displays could be adjusted synchronously via the crown. “When I first started working on the perpetual calendar, none of my colleagues believed me,” recalls Klaus. “The only man who did believe me was Günter Blümlein, my boss, and more importantly, my best friend. When I explained to him that I wanted to move out of haute horlogerie and get into industrial production, he was the only one who supported me with his faith and with his ideas.”

The basic idea behind Klaus' famous chronograph was to make it as simple as possible by using the date indicator function from the basic movement to move the calendar. This, as it turned out, was also the biggest challenge. “You know how in a date indicator watch, you adjust the crown at half position, turn, and voila the date is there! I used the exact same function for the perpetual calendar,” he says. But, this was not the

only function added to the Da Vinci movement. On the completion on the movement, Blümlein suggested the addition of a minute-repeater on top. “See, the ideas were not just mine. It was mostly him and my colleague Giulio Papi, who later joined me to create this 'grand complication',” says Klaus. “He introduced the idea of using a computer to design the minute-repeater on to the movement. This was the first time I got a computer (which was as big as a table, back in 1985), and I learnt how to use the internet”.

Papi, an independent watchmaker, was based in Le Locle, and Klaus was in Schaffhausen. Over a span of four years, the Da Vinci saw numerous adjustments and updates – all communicated over email and constant travel between the two towns, as the two watchmakers strove to complete the wristwatch.

However, it wasn't until an year after the launch of the Da Vinci watch that Klaus realised the potential of his creation. “After the perpetual calendar sold 500 pieces towards the end of 1985, Günter Blümlein arranged a team dinner, and it was only then that I realised and accepted that I had made a winner of this calendar,” he says. Klaus had, finally, and successfully, realised his fascination for creating the impossible.

Over the last five decades, Klaus has become the global face of IWC. He consolidated the company's foundation with the inception of the Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar Chronograph and the launch of Calibre 5000 in the year 2000. He played a pivotal role in the rebirth of the brand. During the Quartz Crisis, Klaus had to work on movements bought from ETA and Jaeger-LeCoultre, as IWC never produced quartz movements. “But I didn't like it,” he says. “We were working only four days a week on these quartz movements, but on Fridays, I was allowed to go to the manufacture and work on something for myself. It was during this time that I made the moon phase and the calendar for the pocket watch. It was like my hobby day”. It was this fascination with mechanical timepieces and Blümlein's faith in Klaus' watchmaking skills, that kept the legendary watchmaker's love for classic watches alive.

Today, though the 82-year-old is officially retired, he still guides and advises the Research and Development department at IWC. Since his first step into the watchmaking industry at the age of 16 to now, Klaus has witnessed dynamic changes in the world of watchmaking. Right from the increasing use of automated assembly lines to assisted technology for handmade watches, he has seen it all . His grand old perpetual calendar was a result of multiple sketches, drawings and calculations. Today, with Computer Aided Design, it is much more easier to get precise and clear

drawings in no time. “When I got my first CAD program, the first thing I did was reconstruct the Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar,” he says. “This was an evolution because it helped me stimulate the functions. But what really did help me the most were the 3D prototypes of my models. I would make these models ten times the size of the original watch to properly try the functions. This was a fun time for me, especially because I was being assisted by my granddaughter who learnt watchmaking at IWC. She helped me operate these machines, and taught me how to make the prototypes. But of course, you still have to, as I like to say it, 'feel with the fingertips'”.

IWC, today, has a good mix of watchmaking professionals who produce some of the best-selling complicated timepieces in the industry. However, creating a balance between the purists, who swore by handcrafted watches, and tech freaks, who ushered in newer ways of watchmaking, wasn't easy. “For a long time, IWC would hire engineers, right out of engineering school,” he says. “Which didn't work well. For watch designing, you need a real watchmaker, which is when I started insisting on hiring young people who are, first and foremost, watchmakers, and then they would go to engineering schools to develop their work further”.

A humble man with a childish chuckle and a lifetime of knowledge behind him, Klaus still looks forward to some of the innovations that technology brings. He's one of the few people who appreciate the addition of smartwatches to the luxury watch segment. “I find it to be a very good thing. I don't own a smartwatch but my grandson does,” he says. “They are two completely different worlds with their own respective audiences to cater to. A smartwatch can never touch an IWC, but it helps cater to this vast segment of individuals who cannot afford a mechanical timepiece from the brand, which is overall a good thing for the industry”. What he doesn't prefer much are the heavily engraved, artistic pieces which are currently making rounds in the industry.

Klaus's most recent watch purchase was for his wife—a diamond-studded Portofino with a mother-of-pearl dial. However, he has always loved traditional, classic collections more than anything else. “The true beauty of a watch lies inside the watch, in its mechanics”, he says.

Klaus has fond memories of his long, arduous journey as a watchmaker, which started at the age of 22, as an apprenticeship under Albert Pellaton. “He taught me things that others learn at engineering school. It wasn't easy to work under him, because he would always say, 'this is good, but it could be better', which made me strive to work better and harder on my movements. All my life, he was my guide, and if he was here today, I think he would have been very proud of my achievements; of our achievements”, says Klaus, stroking the Da Vinci on his wrist.