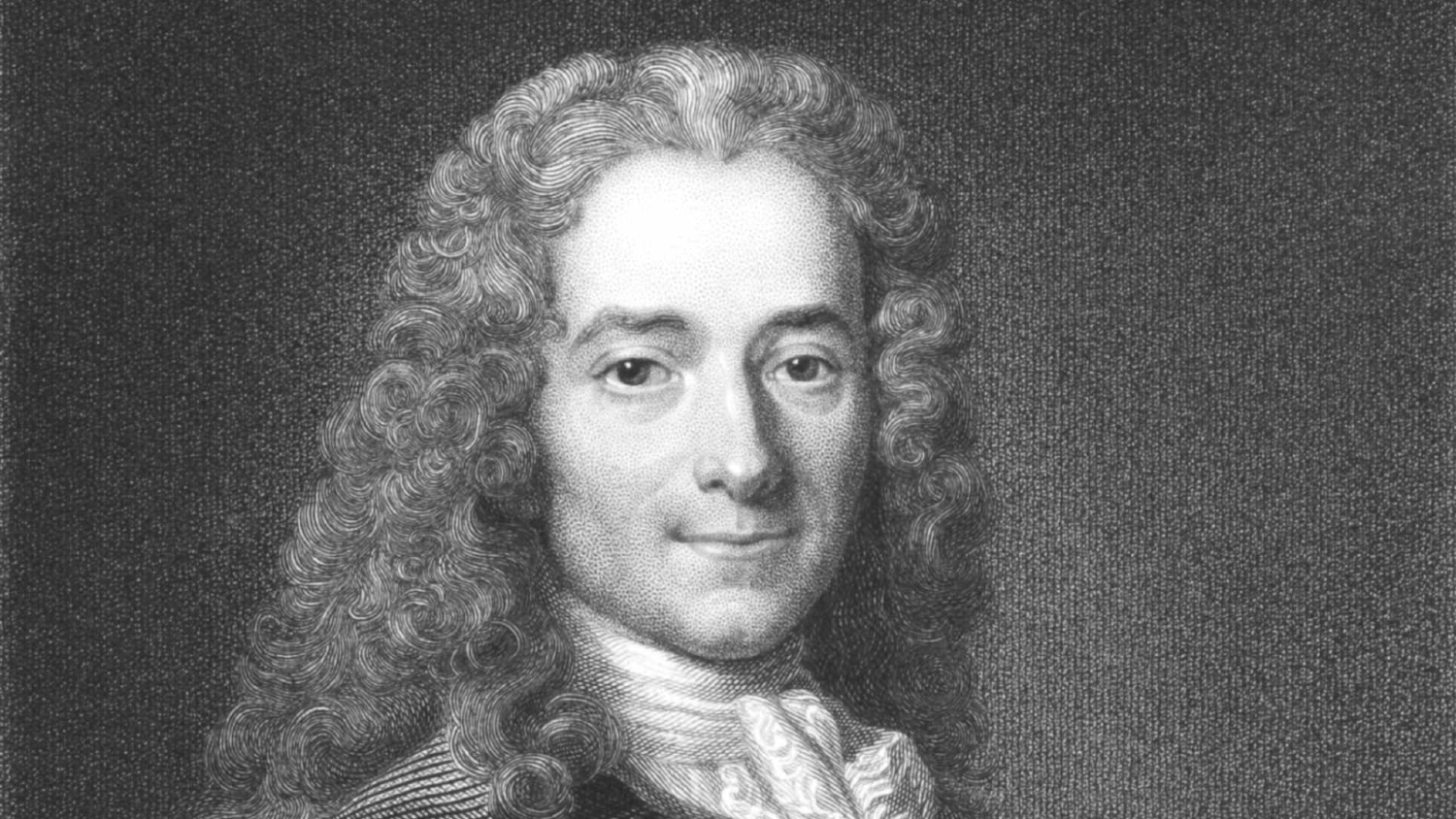

"Here is a very honest price list of the watches. People cannot do better than come to us; we are good workmen and very reliable." These words, from a letter sent in 1770, could have been written by just about any watch salesman in just about any era in watch history. In fact, they were written by a very special watch salesman: François-Marie Arouet, better known as Voltaire. How the provocative French philosopher and most famous author of his time came to write such a letter (to his friend the Comte d’Argental) is one of the least known and least likely tales in watch history.

In it, the elderly and ailing Voltaire, in exile from the French court after supposed disloyalty to France, uses his considerable wealth, influence and energy to set up a colony of watchmakers in the French town of Ferney, in the province of Gex on the Geneva border. That colony turns out watches that are as good as those made in the celebrated watch capital of Geneva, and, thanks largely to the colony’s persistent leader Voltaire, find their way all over Europe (some make it further: all the way to India) and even into its royal courts. The colony continues to make watches for more than 20 years after Voltaire’s death in 1778. Then it disappears, leaving few traces but for the many workaday details woven through Voltaire’s correspondence.

This building (centre of photo) on the Rue de Meyrin once housed a watchmaking atelier

This building (centre of photo) on the Rue de Meyrin once housed a watchmaking atelierIf you drive through the northwest section of Geneva, you’ll see signs pointing the way to a town called Ferney-Voltaire, a virtual stone’s throw away. This is the town, once called simply Ferney, where the 65-year-old Voltaire bought an estate in 1759. Until Voltaire arrived here and set the place humming, Gex province was among the poorest in France.

Voltaire had been banished from the French court for having accepted a post in the court of France’s rival, Frederick the Great of Prussia, in 1750. After a falling-out with Frederick, he sought refuge in Geneva. In 1754, he settled there in a villa he named Les Délices (it is still there) but five years later found himself at loggerheads with the Geneva authorities for having published critical remarks about that city’s hero, Jean Calvin. Voltaire bought the Ferney estate with an eye to leaving the city, and in 1765, when his irritation with Geneva became intolerable—he had myriad complaints against the government, as it had against him—gave up Les Délices to live in Ferney full time.

A repeating watch bearing a portrait of the Duc de Choiseul made in Ferney in 1770

A repeating watch bearing a portrait of the Duc de Choiseul made in Ferney in 1770

Back in Geneva, the class strife that had roiled the city’s politics for more than a century was coming to a head. Geneva society was divided into five rigidly defined classes. All but the top two suffered political and economic oppression. In February 1770, violence broke out when many members of the classes known as the habitants and natifs (who could obtain certain privileges, such as the right to start businesses, only by paying prohibitively high taxes) sought to leave Geneva. During a protest, the Geneva authorities killed several would-be emigrés as a lesson to the others.

Among the discontented habitants and natifs were many of the city’s watchmakers, who numbered in the thousands. Watchmaking had come to Geneva in the 16th century, when Protestant Huguenot refugees from Catholic France, many of them watchmakers, settled there because they were being oppressed in their own country.

Voltaire took the side of the habitants and natifs in their struggles with Geneva’s upper classes. When, following the violence in Geneva, they started trickling over the border into Ferney, he decided to help them. For years he had been offering to harbour in Ferney any habitants or natifs wanting to escape oppression in Geneva. Now, thanks to the bloodshed, they were coming.

The Voltaire chateau

The Voltaire chateauAbout 30 refugees arrived there almost immediately, and Voltaire gave them shelter on his estate. He lent them 100,000 francs interest-free, and turned the theatre on his property into a watchmaking workshop. By April 1770, just a few weeks after Geneva watchmakers began arriving in Ferney, Voltaire wrote to an acquaintance that they had produced their first batch of watches, which were shipped to Spain. By then, the colony had some 40 watchmakers.

Voltaire built houses and workshops along the Rue de Meyrin and rented them out to the watchmakers. By October 1770, there were 40 such buildings.

During that first year, Ferney became such a powerful draw for watchmakers from Geneva that Voltaire crowed about it in a letter to the Marquis de Jaucourt: “All the workers of Geneva would come here if we were able to house them. We must remember that everyone nowadays wants a gold watch, from Peking to Martinique, and that before there were only three great manufacturing centres, London, Paris and Geneva.”

Louis XV ended up on Voltaire’s list of deadbeat watch customers

Louis XV ended up on Voltaire’s list of deadbeat watch customersBy the following year, Ferney had four separate watchmaking companies. The number of firms varied over the life of the colony, but in its first eight years, the period when Voltaire was providing information about the colony in his letters, they included Dufour et Céret, Valentin, Daleizette et Dufour, Valentin et Daleizette and Servand et Boursault. Voltaire did not profit directly from sales by the colony’s watch companies, although he did begin to charge the watchmakers interest on the loans he made to them after their companies started to prosper. Emigrants came not only from Geneva but from farms in Gex province and the Jura Mountains. In time, Parisian watchmakers began sending their sons to Ferney to do their watchmaking apprenticeships because there were fewer temptations and distractions in the modest and quiet little town.

And it wasn’t just watchmakers who settled there. Case makers, enamellers, engravers and gem-setters also moved to Ferney, making it a soup-to-nuts watch centre in the manner of its larger rivals. It turned out both simple watches and repeaters, with verge escapements and often with fusée mechanisms.

The Comtesse du Barry received a dunning letter from Voltaire

The Comtesse du Barry received a dunning letter from VoltaireWithin a few years, the high quality and low prices of Ferney watches had made the town a major supplier to the watch industry in Paris, albeit an anonymous one. In 1774, Voltaire wrote to the Duc de Richelieu that nearly all the watchmakers in Ferney were making watches for Parisian companies, who put their own names on them. (This may explain why there are few extant watches with Ferney-company names on them.)

That year, the famed Jean-Antoine Lépine, a native of Gex province (born in the town of Challex) and watchmaker to Louis XV, set up an office in Ferney, which he placed under the direction of another royal horologist, Joseph Tardy. It is not known precisely what Lépine’s Ferney operation did, but it is further evidence of the strong Paris-Ferney connection. (Some Ferney-made watches contained the slim, single-plate calibers that Lépine invented about the time the Ferney colony was founded.) Earlier, Voltaire had persuaded Lépine to act as his representative in Paris.

There are no reliable production figures for the Ferney colony: Voltaire’s letters are the only source of nearly all information about the Ferney watch business. One year, 1773, the watchmakers there made 4,000 watches, he wrote to one correspondent. Ferney watchmaking seems to have peaked around 1776, the year when Voltaire wrote that 1,200 heads of household were working in Ferney in watchmaking and its related crafts.

It was Voltaire’s relentless advocacy for the Ferney watchmakers, on several fronts, that made the colony so successful. Above all he was an indefatigable and sometimes shameless promoter of their wares. A book about Ferney-Voltaire, Ferney-Voltaire: Pages d’Histoire, written by a committee of the town’s residents, describes his singleness of purpose: “From the earliest days, Voltaire occupied himself [with finding customers] with an incomparable ardor, abandoning for a time questions in which he had until then had a passionate interest. He had just one idea in his head, to sell watches, and all his friends and acquaintances were required to help him in this task.”

He exploited every connection he had and every occasion that presented itself, starting as soon as the first watches were ready. In May 1770, as the marriage of Marie Antoinette to the future Louis XVI approached, he asked his friend, the Duchesse de Choiseul, whose husband, the Duc de Choiseul, was France’s foreign minister, to buy six watches that could be given as gifts to people who entertained at the festivities. The watches were at least one-third cheaper than they would have been if made in Paris or London, and were “very pretty and very good,” he argued in a letter to her. Voltaire’s pitch worked; the duchess took the watches.

Around the same time, he wrote letters to all the French ambassadors in foreign countries asking them to buy Ferney-made watches, explaining that he had started the watchmaking colony, which had the protection of Louis XV, to help the watchmakers after the killings in Geneva. Despite being Protestants, the watchmakers had ample respect for the Catholic religion, Voltaire assured the Catholic ambassadors. He pointed out that if they didn’t want to order any watches, they could help the watchmakers another way: by recommending to Voltaire trustworthy sales agents in the countries where they were posted. With each letter Voltaire included a watch-price list.

Voltaire got into verbal fisticuffs with one ambassador, Cardinal Bernis, after making this request. Bernis was the ambassador to the Vatican, and Voltaire wanted him to find a sales agent for Ferney-made watches in Rome. After ignoring Voltaire for months, Bernis wrote to say that he was sorry, he had done all he could, but Rome just didn’t seem to have any agents Bernis could vouch for.

The world’s most famous intellectual went bananas. “I have seen by your silence, about the colony I have built, that you are not helping me at all. I cannot avoid telling you that you have given me infinite pain.” He complained bitterly that Bernis was the only French ambassador who had not tried energetically to find a sales agent for the Ferney watches.

Voltaire also solicited his friend, the Russian empress Catherine the Great, within months of the watchmakers’ arrival in Ferney. The empress placed an order, and Voltaire shipped to her watches worth twice as much as she had agreed to pay. Pretending that the shipment had been an error, Voltaire wrote to the empress that he had excoriated the “poor artists” who had made the mistake. He nonetheless asked for payment for the entire shipment. Catherine politely complied. Among the watches she bought was one bearing her portrait in enamel. Many were expensive (but not nearly as expensive as they would have been if made elsewhere, Voltaire pointed out, and furthermore were of much higher quality than if they had come from Geneva).

He spent much time dunning customers for payment; some of the richest people in France turned out to be its worst deadbeats when it came to paying the Ferney watchmakers. He sold six watches to Louis XV, but years afterward had still not been paid. He was forced to write a letter to the Duc de Richelieu asking him for payment for the king’s watches. (It’s possible that the payment was withheld because of the poor quality of some of the enamel portraits on the watches, but Voltaire wanted every centime the king owed.)

Voltaire wrote the Comtesse du Barry, mistress of Louis XV, a letter to the same effect, about a different transaction: “The artists of my colony who have, at your request, executed a watch set with diamonds, throw themselves at your feet. I would ask you when settling your affairs to kindly remember my poor colonists.”

He also secured supplies of gold for the colony by intervening with his banker in Lyon. At one point, when the gold stock in Ferney ran low, he gave the colonists 40 gold medals to melt down: they had been a gift from Catherine the Great to Voltaire to thank him for having written a history of Peter the Great.

Voltaire even intervened with the post office, and was able to get free shipping for Ferney watches not just within France but to other countries as well. In 1772, he wrote a melodramatic letter to the postmaster general, thanking him for his help. “If they [your favors] were to cease, my factories would close, my houses that I have enlarged would become useless, and the workers could not reimburse me for the enormous advances I have given them interest-free: I would be ruined.”

He feared equally devastating calamities from changes in the French government’s stance vis à vis his watchmakers, which included favorable tax rates, and lobbied hard to prevent them. In 1771, some months after the colony’s protector, the Duc de Choiseul, fell from power, Voltaire launched a letter-writing campaign aimed at winning the good graces of de Choiseul’s successor as foreign minister, the Duc d’Aiguillon. Voltaire wrote to d’Argental, asking him to find out what d’Aiguillon thought about the colony (Voltaire had himself written to d’Aiguillon but had received no answer): “My colony is no longer protected, and this is most alarming to me. I’m just about to see all of my work destroyed. Can’t you say a word [to d’Aiguillon] about it? It would surely be very easy for you to find out, in the course of conversation, if he is favorably disposed or not.” A few days later he wrote to d’Aiguillon’s wife, the Duchesse d’Aiguillon, to ask her to remind her husband about his request for continued protection for his watchmakers.

Catherine the Great was one of the colony’s best customers

Catherine the Great was one of the colony’s best customersUltimately, Voltaire couldn’t preserve his watchmakers’ government-granted privileges. In 1776, the colonists’ tax exemptions were revoked and the Ferney watchmakers had to pay as much as any other Frenchmen. Voltaire responded with his characteristic doomsaying, writing in a letter: “Our colony of Ferney is not so happy, it is persecuted, almost annihilated...The five hundred thousand francs that I spent on the houses I built are just five hundred thousand francs thrown into Lake Geneva.”

In fact, the colony survived for an entire generation after that.

Voltaire himself lived just two more years. He left Ferney for Paris in February 1778, hoping to get two of his plays performed at the Académie Française, and died in Paris four months later at age 83.

There are few surviving artifacts from the Ferney watchmaking colony. In Ferney, two of the buildings that once housed watchmaking workshops still stand on Rue de Meyrin. There are a few Ferney-made watches in museums (but none in Ferney itself).

Instead, the colony has been kept alive in print: in Voltaire’s letters and, rather unexpectedly, in a poem by W.H. Auden called “Voltaire at Ferney,” whose first lines read: “Perfectly happy now, he looked at his estate./An exile making watches glanced up as he passed/And went on working...

This story first appeared in WatchTime India's July-September 2012 issue.