We’ve heard the name. We know the stories. An overnight conception. A design scrawled on a napkin. Mention the name Gérald Genta and the mind can’t help but conjure images of two of the most iconic horological births.

Spanning over half a century, his long and illustrious career has been the subject of much discussion, specifically the important designs that punctuate it. Even as the most lauded watch designer of all time, the full scope of his contributions to horology aren’t immediately obvious. By his own estimation he completed some 100,000 designs over half a century. Forty plus years later, the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak and the Patek Philippe Nautilus remain cornerstones of their respective brands.

Using geometry as his muse, Mr Genta built a career flirting with the thin line separating the conventional from the offbeat, a contrarian sorcery that wove through much of his work.

There’s truth to the old saying that art imitates life. Indeed, the origin story of a creative work draws from the life experience of its creator. At its core art is, technically speaking, the physical expression of the sum of the artists experiences, observations and natural talent passed through the personal filter of perception and feelings, then contextualised at the moment of externalisation. Genta’s work evolved as he did in a cycle of experimentation that gave rise to new concepts, then built upon and abandoned them in a continuous progression, thus his later work is, at first glance, a completely different animal than his early creations. To appreciate what came at the end one must take stock of what transpired at the very beginning. Our journey begins in 1931.

It’s difficult to imagine a more fitting setting for Mr Genta’s earth-side debut than the city of Geneva, Switzerland. As a young man he found himself drawn to the arts and took to painting and sculpture. Although he shared his hometown with watchmaking juggernauts, his aspirations were not initially horological in nature - they lay in jewellery. In 1950 he completed his training as a goldsmith and began looking for work. As fate would have it, a downturn in the global economy meant that jewellery designers weren’t in high demand, forcing him to turn his skills elsewhere. His fortuitous move to watch design was one borne of necessity. It’s no small irony that, if left to his own devices, the great watch designer wouldn’t have designed a single watch.

Freelancing brought him contracts with watch brands and through them dial and case makers. It’s not uncommon to spot the distinctive geometry of Genta on a dial mounted inside a generic case. In 1953 he developed a particularly close working relationship with a modest watchmaking house nestled in a small Swiss village at the foot of the Jura Mountains. Audemars Piguet was founded in Le Brassus in 1875, and although they had been making watches for over three quarters of a century, their small family run operation numbered less than 50 employees. This type of arrangement proved ideal for Genta who was selling his designs for 15 francs a piece. He needed the work, and they needed watches that stood out from the crowd. Mr. Genta was up to the task.

The 1950s saw Audemars Piguet shift focus from functional to aesthetic complications. The development of the ultra-thin wrist watch that had begun in the early part of the 20th century was now gaining traction, and companies had begun devoting substantial resources to engineering the thinnest watches possible. By 1960 AP had fazed out the venerable 13 ligne Valjoux “VZ” in favour of thinner calibers. The 9ML, originally launched in 1938 and clocking in at only 1.64mm high, was reworked and launched in 1953 as the caliber 2003 and would go on to enjoy an impressive 50 year run, ending production, ironically, in 2003.

1953 was a seminal year for the twenty-two year old designer, marking the beginning of a decades-long partnership with Audemars Piguet. One of the first of Genta’s Audemars Piguet branded designs to leave the workshop is reminiscent of the work of architect Frank Lloyd Wright. A rectangular case set lengthwise is surrounded by a thin bezel and flanked on either side by shallow gold steps. To mark the hours, Genta chose applied gold batons, peaked in the centre, that extend radially into the corners as they make their way around the dial. Inside the watch beats a last vestige of AP’s old guard, a 9/10 RSQ, a particularly striking tonneau-shaped movement with brilliant Côtes de Genève and hand engraved nomenclature flashed in gold. Engraving the brand signature and other details onto the movement by hand was once standard practice at Audemars Piguet, but as processes were refined the practice was all but phased out in favour of less costly, more efficient machine stamping. Small rectangular lugs protrude from the top and bottom of the case, rounding out a generous helping of right angles.

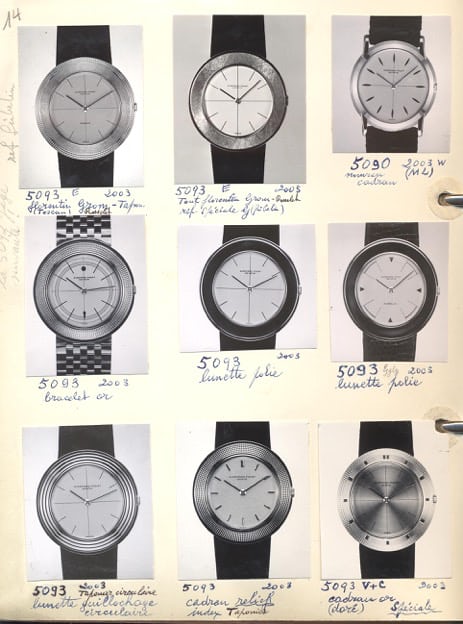

If there existed a single reference that embodied the devil-may-care spirit Genta was injecting into the ranks at Audemars Piguet, it was the reference 5093. Dubbed the “Disco Volante”, or “Flying Saucer” by Italian collectors for obvious reasons, it was Audemars Piguet’s most audacious foray into ultra-thin watchmaking, a characteristic Genta chose to highlight by shifting focus from the dial, where tradition dictated, to its broad, knife-thin bezel. He did this by adorning it with a vast array of patterns and ornamentation; examples are found bearing rows of engine turned Clou-de-Paris, embellished with precious stones or florentine’d, and ran the full gamut of precious metals. The bezel wasn’t always out to steal the show however, and as bezel designs ranged, so did the dials. Some were simple, others were hand painted masterpieces flashed with multiple tones of gold gilt. A page from the Audemars Piguet archives highlights the extreme variation in design that the reference 5093 encompassed. Note the machined bezel of the pictured black dialled 5093 and it’s obvious similarity to the inner bezel of Universal Geneve’s Polerouter, also designed by Genta and launched by the brand in 1954. Common themes and elements appear throughout Mr Genta’s work.

Far from the grand spectacle of the 5093 exists a master class in the art of restraint - the reference 5007, specifically this reference 5007. Produced on the benches of Audemars Piguet in 1959, the example we see here doesn’t defy convention as the Royal Oak did. It prunes away the unnecessary, streamlining the design to its most basic elements. Even in Genta’s early work his unique relationship with geometry emerges. Its round 35mm white gold case, small by modern standards, gently turned back lugs and thin, sloped bezel are minimalist; the concept of less, elevated to provide a dose of serenity at the turn of a wrist. The slim, nearly invisible bezel guides the focus of its wearer to the slender machined batons. Look long enough and you might catch an elusive flash off the black polished facets. Simple. A watch like this distills timekeeping to its most essential form. Nothing wasted. Supreme efficiency. In plain English, it all coalesces into a great looking watch. But it doesn’t stop there. Inside is a 13”’ VZASC, one of the very last 50 to leave the factory in 1959, the movement’s final year of production. A final nod to the end of an era.

Increasingly esoteric designs were also being explored. Asymmetry, a new concept in the world of horology, presented in stark contrast to the classic, refined and benign forms of previous decades. Round or right angled, watches made prior to the 1950s were just about guaranteed to be comprised of equal and proportionate opposing dimensions. Shedding the rules of symmetry allowed Genta to fully explore the watch as an object of art, bound only by the necessity of keeping and telling the time. Here he gently courts the Japanese design principle of “fukinsei” with a case resembling a capital ‘C’ stretching from left to right to swallow up the round watch head, as if Pac-Man had discovered a sudden taste for horology. The constituent parts are unequal, but the open mouth of the ‘C’ on the right is balanced by a slight taper as the eye moves left. It’s clear that the inner section of the two tone dial began as a pure and innocent circle before Genta’s tectonic shift of left and right hemispheres moulded the slender indexes to their will.

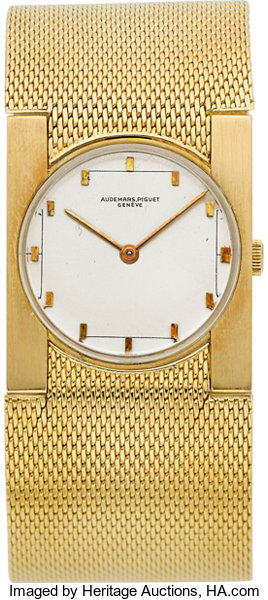

The oddball “H”. Is is a circle, or is it a square? Here Genta pits both shapes against each other, each vying for dominance over the visual strata. The Bauhaus vibes are not subtle and are executed in distinct Genta fashion. We see again the slender peaked batons for hours, this time interconnected with thin black lines forming a peripheral frame. This clever dial layout serves a dual purpose; not only does it add depth to a design that would otherwise risk being a bit austere, but serves as a spectral continuation of the outermost “H”-like linear structure. A square inside a circle inside a square. In the centre lies a set of Audemars Piguet’s ubiquitous baton hands.

Examples of this reference are found in both yellow and white metal, and fitted with both straps and bracelets. It’s also worth noting that although examples fitted with generic straps and bracelets have been documented, an example with a fitted bracelet that could have been born with the watch was sold by Heritage Auctions in May of 2014. If this watch was indeed originally sold with the bracelet fitted it could very well have been Mr Genta’s first design to feature an integrated bracelet, predating the Royal Oak by over a decade. It’s also quite possible that the bracelet was an individual made-to-order item hand crafted for an especially imaginative customer.

An examination of Mr Genta’s work yields many realisations and an understanding that without him, the landscape of the Swiss watch industry of today might look very different. His legacy has become far greater than the sum of his designs, captivating as they are. He gave us a reason to fall in love with watches again in that most crucial moment when the fate of an industry hung in the balance, and fall in love we did, and still do.