When Blancpain successfully defined the basics of the modern dive watch in 1953, the company was already 218 years old. For the last (almost) 70 years, the Swiss brand has not only been deeply connected with the history of diving and underwater exploration, it has also become a force in protecting the biodiversity of the oceans. The 2014-founded Blancpain Ocean Commitment initiative (BOC) is a unique program in the watch industry that has already helped a number of environmental initiatives get off the ground (some of them already underway before BOC was launched). The latest example is a project with the Mokarran Protection Society to measure and identify great hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna mokarran) in French Polynesia, and to lay the essential groundwork for more effective conservation efforts in the future. The watch dedicated to this project is the first Fifty Fathoms Bathyscaphe with a green dial and bezel, limited to just 50 pieces (Ref. 5005-0153-NAB A). It is also the brand’s first no-date version with a 43.6-mm case.

Blancpain – A Member of the Diving Community since 1953

Jean-Jacques Fiechter (born May 25, 1927), Blancpain’s Co-CEO from 1950 to 1980 and an avid diver, was one of the first to realize that — in addition to masks, fins, depth gauges and diving tanks — divers would also need a specialized timing device, a reliable instrument that could indicate the dive time at a glance. In the 1950s, Fiechter began experimenting with what would become the Fifty Fathoms in 1953, implementing new ideas for the caseback and crown gasket that would much better protect the automatic timepiece from the constant pressure of water, resulting in patents for both designs. In addition, and also due to the fact that manual chronographs could not as securely be operated underwater at this point in watchmaking history, Fiechter and his team also introduced the iconic unidirectional bezel that would allow the watch’s wearer to better track how much time was spent underwater.

The Fifty Fathoms proved to be so reliable and robust that several naval forces equipped their divers with the Blancpain model over the coming years, including the French, Israeli, Spanish, German and American Special Forces. In fact, the watch only required the addition of a soft iron antimagnetic case in order to convince French secret agent Robert “Bob” Maloubier (Feb. 2, 1923 – April 20, 2015) to supply the French combat swimmers with watches and thus launch the military career of the Fifty Fathoms. But while professional divers still represented a comparatively small market potential, the increasingly popular category of recreational diving would be the key to the model’s commercial success. “The Bathyscaphe was the next step that allowed a new audience to get in touch with diving and discover the underwater world,” Fiechter recalled in 2013, when Blancpain launched the first model of the current Bathyscaphe to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the Fifty Fathoms collection. He added, visibly moved, “It’s almost a miracle that, 60 years after, I find another passionate diver at the helm of the company.”

The Renaissance of the Quintessential Diver

Marc A. Hayek (born Feb. 24, 1971) has never made a secret out of his passion to rather “be underwater than around meeting room tables,” if given a choice. As Blancpain’s CEO, he had already successfully reintroduced the current generation of the Fifty Fathoms in 2007 (following the smaller, 50th anniversary edition from 2003), which also saw the introduction of a new manufacture movement (Caliber 1315) with 5-day power reserve. The relaunch of the Bathyscaphe in 2013 was followed by the start of the Blancpain Ocean Commitment initiative in 2014 with the Fifty Fathoms Bathyscaphe Flyback Chronograph Ocean Commitment I (Ref. 5200-0240-52A), powered by the new F385 movement and the brand’s first use of high-tech ceramic for the case.

Following the success of this watch and the positive message it conveyed, Blancpain extended the initiative in 2016 with the Ref. 5200-0310-G52A Bathyscaphe chronograph with blue ceramic case and unveiled in 2018 the third BOC timepiece (Ref. 5008-11B40-52A). All three editions were limited to 250 pieces and included an additional donation of €1,000, which was made for each watch in the series in addition to the annual funding granted by Blancpain. Collectors of one of these limited-edition watches received a corresponding hand-numbered copy of the Edition Fifty Fathoms book. The purchase of a limited edition Ocean Commitment watch also comes with membership to the Blancpain Ocean Commitment Circle, giving access to exclusive advantages, including invitations to private BOC events and conferences regarding ongoing scientific expeditions financed by Blancpain.

Even though the Mokarran Limited Edition is not officially a BOC edition, Blancpain has decided to include an access code to join the BOC Circle and a framed photograph from the January mission. This inclusion is another step to raise public awareness and achieve the brand’s goals of helping preserve and protect the world’s oceans. Or in the words of another famous owner of the Fifty Fathoms, Jacques-Yves Cousteau (June 11, 1910 – June 25, 1997), “People protect what they love.”

In the last 10 years, Blancpain has already co-financed 19 major scientific expeditions, participated in the doubling of the marine protected surface area around the world, and presented several award-winning documentary films, as well as underwater photo exhibitions and other publications. The inventor of “the first modern diver’s watch in the world” has also been a founding partner of the National Geographic Pristine Seas project, and has been supporting the initiative for five years (2011 – 2016). Blancpain also played an instrumental role in becoming involved with Laurent Ballesta’s Gombessa project, which is devoted to the study of some of the rarest and most difficult-to- observe marine creatures and phenomena, and has also been active in supporting the World Ocean Summit organized by The Economist, the World Oceans Day, which takes place every year at the United Nations headquarters in New York City, the Hans Hass Fifty Fathoms Award, and many others.

What makes Blancpain’s engagement so unique is, first of all, the brand’s transparency about which projects are funded (watch brands rarely disclose the exact amount that is raised with a limited edition, and in this case, the funding is indeed more than substantial), and secondly, the brand’s own involvement in these projects that usually goes beyond providing just financial resources. For this project, Marc A. Hayek personally supported the Mokarran Protection Society over several days, using his own camera equipment and rebreather (a rebreather allows longer dive times and greater maximum depth, maximizes a diver’s no-decompression limit, and creates far fewer, if any, bubbles and almost no noise underwater, which makes them significantly better for tasks like this) to support the team in Rangiroa. Or in other words, how often do you find the CEO of some of Switzerland’s most significant watch brands below 200 feet, waiting with a camera for hours for a great hammerhead to appear?

Protecting the Great Hammerhead Shark Requires an Understanding of the Species First

The newly founded Mokarran Protection Society sees itself as an “alliance of competences to better understand the great hammerhead shark.” The team has been operating from December 2019 to January 2020 from the Rangiroa Plongée dive centre, which has in itself been supporting different ocean conservation projects since it began operating in 2008. As with previous projects, Blancpain has included an additional donation of $1,000 per watch.

The Mokarran Protection Society, which consists mostly of volunteers, has been working with a noninvasive technique called laser photogrammetry, basically a panel with two parallel lasers and a digital camera, that allowed them to project laser markings to measure, reliably identify and track individual sharks over time. This in return will now lay the groundwork to improve activities linked to the conservation of the species. Marc A. Hayek said, “When I first came to Rangiroa in 2012, I immediately fell in love with this beautiful creature. At the same time, I realized that we barely know anything about the species and its behaviour. Compared to other projects we supported in past years, this project is based on volunteers, and aims to try to find out more about the hammerhead sharks here. First step was to make sure that the great hammerhead is officially recognized and registered in this area, and to create a database for other scientists to continue from here, some who are already part of the team, like Tatiana Boube, who I am extremely happy to support early in their careers with this project.” He added, “It is absolutely urgent to start this work now; I initially was afraid we would only find two, three different sharks. It now looks like there are a bit more than I had hoped, and already that a lot of the hammerhead’s [observed] behaviour we thought we knew might have to be revisited.”

But, for Hayek, there is also a much more personal connection to the hammerhead shark. “I never intended on becoming a dive instructor, but in order to be able to go that deep with the camera, I had to be certified as a dive professional. On my final diving exam here in the pass a couple of years ago, I encountered the largest hammerhead I’d ever seen. He swam right next to us, made eye contact and then disappeared into the deep. When I fully realized how significant this encounter was, it felt a bit like a rite of passage. I was given the okay to dive in the pass here, which was both humbling and extremely moving.”

The Next Chapter of the Bathyscaphe

The current three-hand Bathyscaphe from 2013 took its direct inspiration from the model that debuted in 1956, which was intended to be a more wearable, “civilian” version of the bigger, military-designed Fifty Fathoms that had preceded it three years earlier. Since its launch, the Bathyscaphe has quickly grown into a sub collection of its own, with chronograph models (2014), a Day Date ’70s and a Quantième Annuel and Quantième Complet Phases de Lune version (all 2018), and different diameters and case materials, including titanium, Sedna gold, ceramised titanium, steel and ceramic.

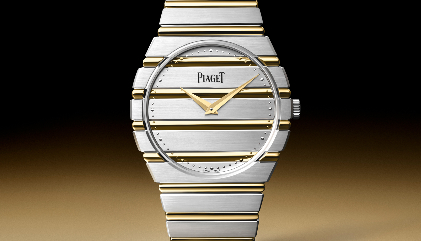

The newest version of the Blancpain Fifty Fathoms Bathyscaphe brings a new colour to the collection: it is distinguished by its green dial and unidirectional bezel with a matching green ceramic insert with markers made of Liquidmetal, a proprietary material used in several other Blancpain watches and by other brands within the Swatch Group. The luminous dot index at 12 o’clock is a faithful reproduction of the one used on the original Fifty Fathoms watches of the 1950s. The 43.6-mm-diameter case is water resistant to 300 meters and made of black ceramic with sweeping beveled lugs and a satin-brushed finish.

The new sunburst-finish green dial features a central hour and minute hand that are based on the look of the vintage original; the date, usually located in a small window at 4:30, has been removed for a puristic look, a first for the 43.6-mm version; and the large, red-tipped central seconds hand serves a utilitarian purpose for those diving with this watch, as an indicator that it is functioning.

At 43.6 mm in diameter and 13.8 mm thick, the Bathyscaphe is certainly not a small watch. Yet, its understated, reduced design never lets it appear big or out of place on a wrist. The same goes for the conveniently large crown that screws down for security.

The watch is equipped with Blancpain’s self-winding Caliber 1318, a robust movement with 204 components, 35 jewels and a high level of chronometric performance. Its three series-coupled mainspring barrels provide an impressive power reserve of five days. The movement, visible through the watch’s clear sapphire caseback, has a balance spring made of silicon, a material that features several key properties — low density that makes it particularly light, strong shock resistance, and imperviousness to magnetic fields — which help to optimize geometry of the balance spring, thereby improving the isochronism of the movement and ultimately the precision of the watch. Blancpain’s 1318 is also fitted with a Glucydur balance wheel with square-head gold micrometric regulating screws to improve precision and allow for efficient adjustment. The gold oscillating weight comes with an engraving of a hammerhead shark.

While undoubtedly more brittle than metal, ceramic offers a couple of advantages that are worth mentioning. It’s a corrosion-resistant, lightweight material that offers a great look for a dive watch and is extremely comfortable to wear. More importantly, since it hasn’t been coated with an additional layer of color, it will keep its black color. The same goes for the missing date: while being one of the more popular complications on the market, collectors have quite often asked for a different position, or even better, a more puristic no-date version. The green used for the bezel and dial is simply a thing of beauty: depending on the lighting, the color ranges from emerald green to almost black, making it one of the visually most attractive versions in the collection. Underwater, the three-hand watch couldn’t be more legible, especially thanks to its puristic dial design.

On a more personal note, the Bathyscaphe from Blancpain has quickly become a personal favorite after its launch in 2013, especially thanks to its understated, clean design and incredibly rich heritage. Additionally, Blancpain has carefully worked on the evolution of the range, making sure that the design would get enough time to be established as the classic it is. With this version, Blancpain has not only managed to introduce a new colour, but to create one of the few watches that would most likely leave you completely satisfied, should you ever find yourself marooned on a remote isle — or underwater on a quest to see the great hammerhead shark yourself.

Last but not least, the supported program with the Mokarran Protection Society has already started to make a difference, and it was impressive to see how efficiently the whole team and project were set up with all hands on deck.

Time To Act

Blancpain kicked off this special project in May 2019, and the first prototypes were available for a hands-on in January 2020. Due to its limitation to only 50 pieces, Blancpain has agreed to make 10 pieces available on a first-come, first-served basis exclusively to U.S.-based readers of WatchTime magazine. If interested, please send an email to office@watchtime.com and we’ll gladly help you coordinate with the nearest Blancpain boutique to make sure this isn’t the last time you’ve seen the Fifty Fathoms Bathyscaphe Mokarran Limited Edition

To learn more about Blancpain’s Ocean Commitment, visit blancpain-ocean-commitment.com

The Great Hammerhead And Rangiroa

Rangiroa, often called the “infinite lagoon,” is the largest atoll in the Tuamotu Archipelago, a French Polynesian group of almost 80 islands and atolls, which is forming one of the largest chains of atolls in the world. It is located about 220 miles northeast of Tahiti and is home to about 2,500 people. Rangiroa is, together with Fakarava in the Tuamotu islands, regarded as a major underwater diving destination because of the lagoon’s crystalline waters and abundant marine life with over 800 species, especially big marine life and one of the highest concentrations of sharks in the world. Jacques-Yves Cousteau (June 11, 1910 – June 25, 1997) ranked it among “some of the most beautiful scuba diving spots in the world.” One reason for this: each high tide creates a strong incoming current while each low tide creates a strong outgoing current in the atoll’s two passes, Tiputa and Avatoru. When the current is flowing inward through Tiputa Pass, sharks gather at the entrance to the Tiputa Pass. Large manta rays, eagle rays, turtles, moray eels, schools of barracuda, grey reef sharks or black tip sharks can also be encountered, as well as tiger sharks and hammerhead sharks. Last but not least, Rangiroa is also home to a large group of bottlenose dolphins. In January, large numbers of eagle rays gather in the Tiputa Pass, as well as hammerhead sharks. Whales are generally present from August to October; the concentration of hammerhead sharks and eagle rays is higher from January to the end of March.The great hammerhead (Sphyrna mokarran) is the largest species of a total of nine hammerhead sharks, attaining a maximum length of 20 feet and weighing up to 1,000 pound. It is found in tropical and warm waters worldwide, inhabiting coastal areas and the continental shelf. The great hammerhead can be distinguished from other hammerheads by the shape of its “hammer” (called the “cephalofoil”), which is wide with an almost straight front margin, and by its tall, sickle-shaped first dorsal fin. Hammer-head sharks can sense electromagnetic fields, and their wide-set eyes give them a better visual range. A solitary, strong-swimming apex predator, the great hammerhead feeds on a wide variety of prey ranging from crustaceans and cephalopods, to bony fish, to smaller sharks and rays. Unlike scalloped hammerhead sharks, great hammerhead sharks are solitary and migrate long distances upward of 756 miles alone.

Thanks to their impressive size, great hammer-head sharks are not preyed upon by other marine animals, but are vulnerable to over- fishing (even worse, they only reproduce once every two years). They are caught incidentally and commercially targeted for their fins. As of November 2018, the independent International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN) sees the species as critically endangered, having suffered some of the most severe reported population declines of any species of sharks. To make matters worse, there is very little known about the behaviour, movement patterns, population and biology to implement the correct management strategy to protect the species. Nevertheless, French Polynesia created the world’s largest shark sanctuary of 1.5 million square miles of sea on Dec. 6, 2012. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), also known as the Washington Convention, added hammerheads to their list in March 2013.

Unsurprisingly, sharks are a constant presence in the life and culture of Polynesian peoples. The ma’ohi lived with the ma’o in harmony (the great hammerhead’s Tahitian name is “ma’o tuamata”).