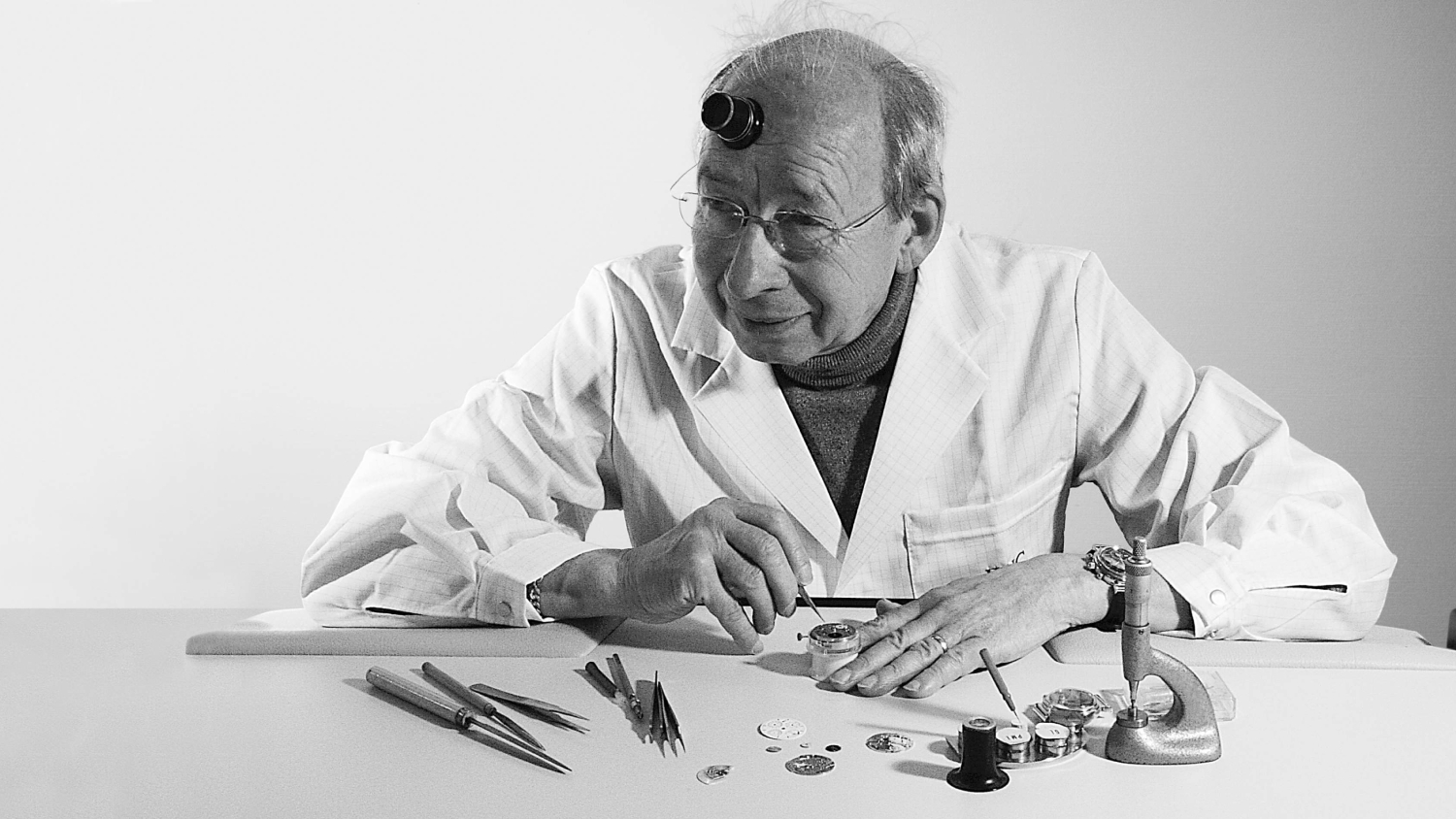

Not every watchmaker can travel anywhere in the world to discuss watches and technology, levers and gears, escape wheels and balances, and have people in the audience hang on to his every word. But not every watchmaker is Kurt Klaus, the man who has created designs for IWC Schaffhausen since the 1970s and who to this day instills a passion all over the globe for the art of fine watchmaking. In Asia, the 91-year-old watchmaker is treated like a celebrity: after a presentation in which he explains, step by step, the basic functions of a mechanical watch movement, initiates his listeners into the secrets of his Perpetual Calendar, and extolls his fascination with mechanics, audience members line up patiently for an autograph. It is a reminder that Klaus, who has spent so much of his career seated at a quiet workbench, has become an eloquent ambassador for IWC, the company with which his designs have become synonymous.

Klaus had always enjoyed horology, and that interest led him to complete a four-year degree at the watchmaking school in Solothurn, Switzerland. He began working for IWC, based in Schaffhausen, two years later, in 1957, because he wanted to stay near his hometown of St. Gallen. He quickly became a specialist in the repair of older watches and became the “go-to” guy for difficult repair jobs. He often had timepieces on his workbench that were 100 years old or older.

Kurt Klaus

Kurt Klaus

“This is how I came to know the philosophy of IWC from the bottom up, and experienced everything about the spirit of quality at IWC,” Klaus recalls. Soon, Albert Pellaton—technical director, head of production and designer at IWC— took the young Klaus under his wing, becoming his mentor. “He introduced me to design. It was difficult because he was so very demanding,” says Klaus. But there was one thing Pellaton was not able to prepare his protégé for, and that was the quartz crisis in the 1970s. Pellaton, who died in 1976, never saw the full consequences that the rise of lower-priced, quartz-powered timepieces had on the Swiss watch industry, but Klaus remembers it well.

IWC countered the quartz crisis with complicated pocketwatches. Pictured here is Klaus’s Ref. 5450, a Schaffhauser Savonnette with calendar and moon-phase, from 1979

IWC countered the quartz crisis with complicated pocketwatches. Pictured here is Klaus’s Ref. 5450, a Schaffhauser Savonnette with calendar and moon-phase, from 1979At that time, the production of mechanical watches at IWC fell dramatically. Klaus remembers a point when there were no new orders at all, and how the company was forced to shorten work hours. Some watchmakers took other work making frames for model airplanes or tiny, silver automobile models just to get by.

IWC eventually adapted to the changes, purchasing quartz movements and casing them. Klaus’s job during this time involved selection of movements, quality control and assembly. The work was so simple compared to the technical challenges of mechanical watchmaking that he went looking for a more interesting occupation in his free time. On Fridays, when shortened work hours closed the company, Klaus would return to the empty workshop and tinker with mechanical pieces.

The Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar, presented in 1985, is also equipped with a chronograph and moon-phase

The Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar, presented in 1985, is also equipped with a chronograph and moon-phase

When IWC management discovered Klaus’s main project, a pocket watch with a complete calendar and moon-phase, it offered to put his creation into serial production. The company permitted Klaus to produce 100 pieces of what became the first truly complicated IWC watch. In 1977, this exceptional timepiece was presented at the Basel watch fair and was a complete success, according to Klaus, whose enthusiasm about it is evident even today. “All 100 pieces were sold by the second day,” he says.

Klaus considers that success to be a shot in the arm for the mechanical watch. He says, “We made sure we had given that watch something that a quartz watch could not do. And we wanted to awaken a passion for mechanics.” Klaus continued building other interesting mechanisms. About two years later, the IWC staff began returning to full-time work, even though their numbers had dwindled from 300 to 150 and quartz watches had become a part of the brand’s portfolio. By the end of the 1970s, IWC was once again making watches, including chronographs, with mechanical movements.

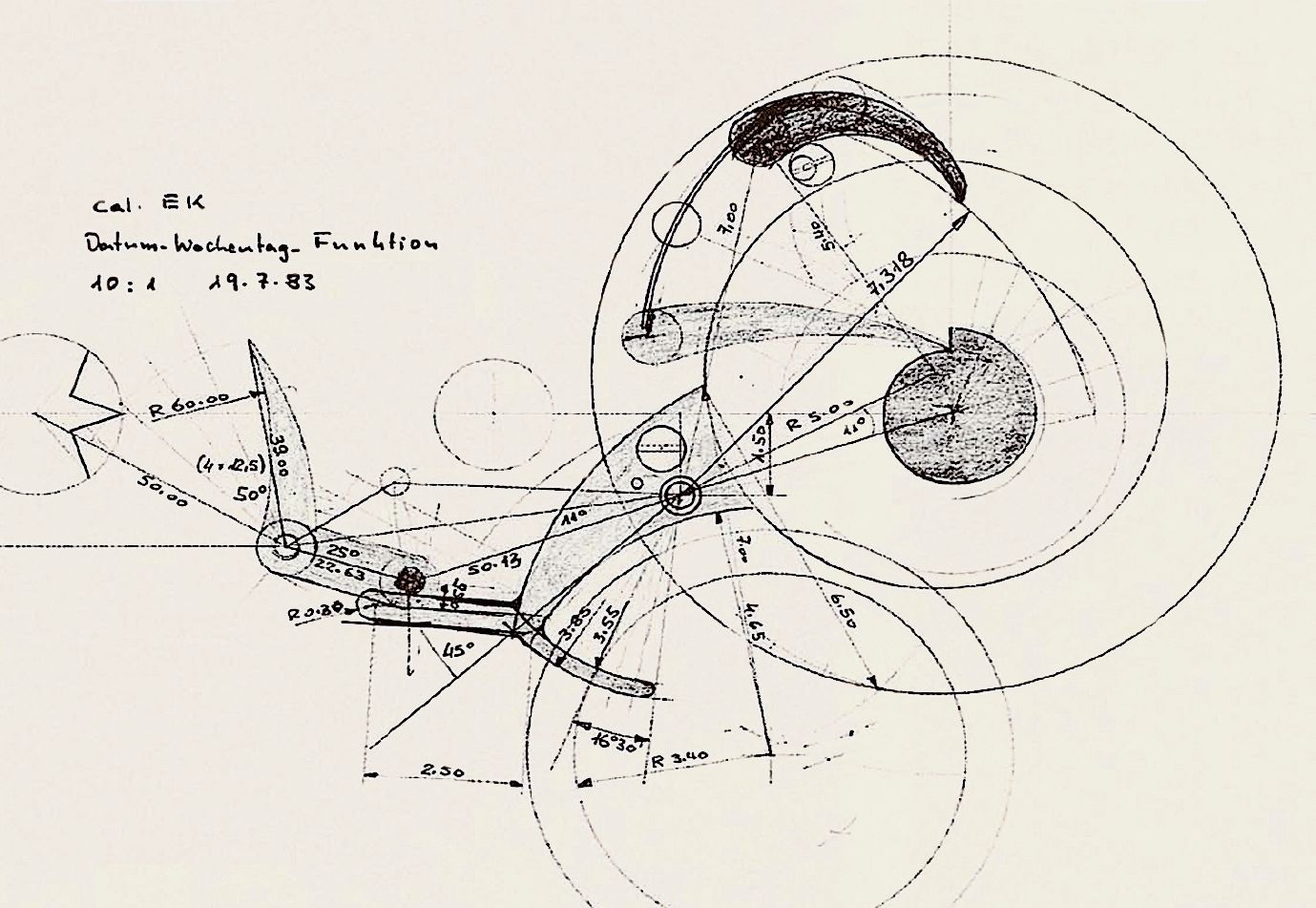

Klaus’s most important project had its origin in the early 1980s, when the head of IWC, Günter Blümlein, asked him to design new wristwatches. Klaus set a high goal for himself—a perpetual calendar that would be simple to operate and one in which the wearer would not have to be concerned with individual calendar settings. He wanted to design an autonomous mechanical system that would ensure that the advance of the 24-hour wheel at midnight was linked to all the other calendar indications so that they all advanced simultaneously and instantaneously. But how could the tiny motion of the date finger on the base movement be transferred to the day, date, month and year indicators? His solution was both simple and ingenious. The changing positions of the date indicators were transferred to a system consisting of cams, levers and wheels so that the calendar function would always take into account the length of different months and even leap years. The system also included the so-called “century slide,” which ensures that even for centuries to come, the first two digits of the year will be correct.

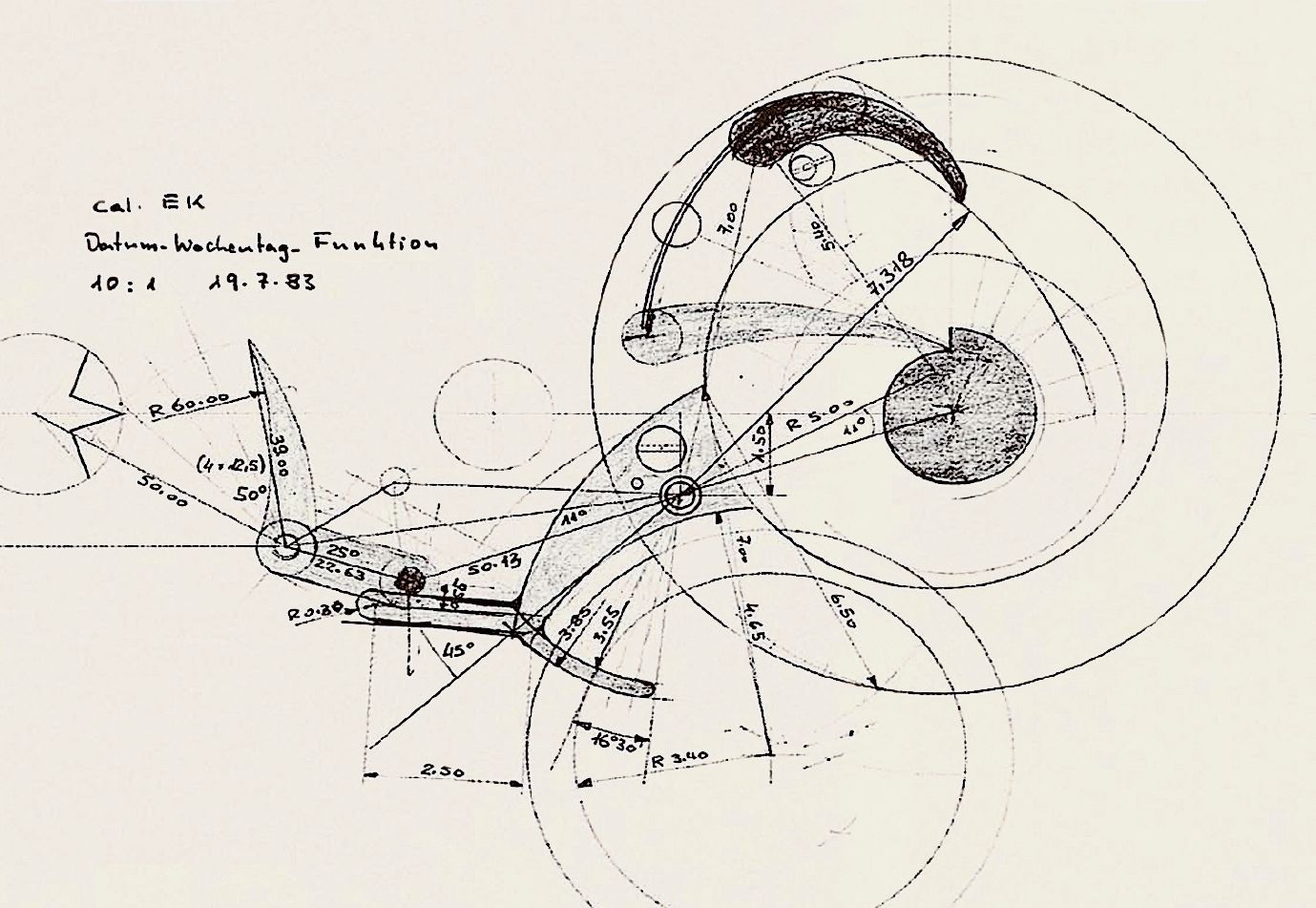

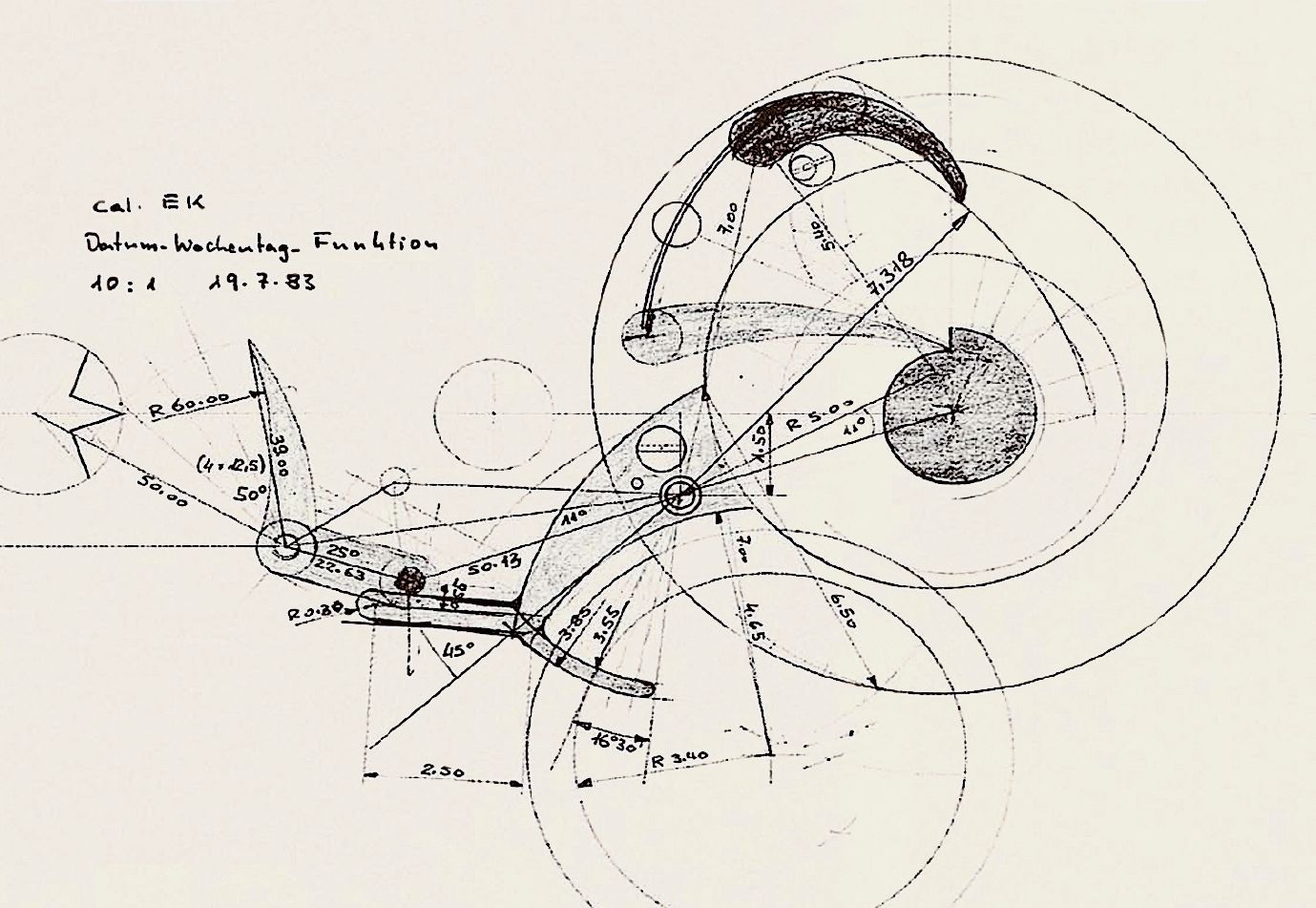

An early sketch of Klaus’s Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar module from 1983

An early sketch of Klaus’s Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar module from 1983The watch had another unique feature. If allowed to wind down, most perpetual calendars require a complex resetting process that involves the use of correction pins and pushers. Klaus’s watch could be adjusted simply by turning the crown to advance the days because all the indications were synchronised.

For several years, Klaus worked on the new mechanism and made calculations based on logarithms, drew designs on his drafting table and implemented those designs on the workbench where he made his own wheels and cut the gear teeth. Klaus worked through the entire night before the watch’s presentation at the Basel Fair in April 1985. He finished in the early morning hours and drove to Basel, arriving at the IWC booth only 30 minutes before the start of the fair. The small suitcase he carried contained three prototypes of the first Da Vinci watch with a perpetual calendar, housed in elegant gold cases. The watch received a very warm reception, and visitors to the fair marveled at Klaus’s technical achievement.

Customers quickly placed their orders and in August 1985 the first of the watches was delivered. Five hundred pieces were completed by the end of that year.

The first Portofino, with complications designed by Klaus, debuted in 1981: the model was the basis for the current series

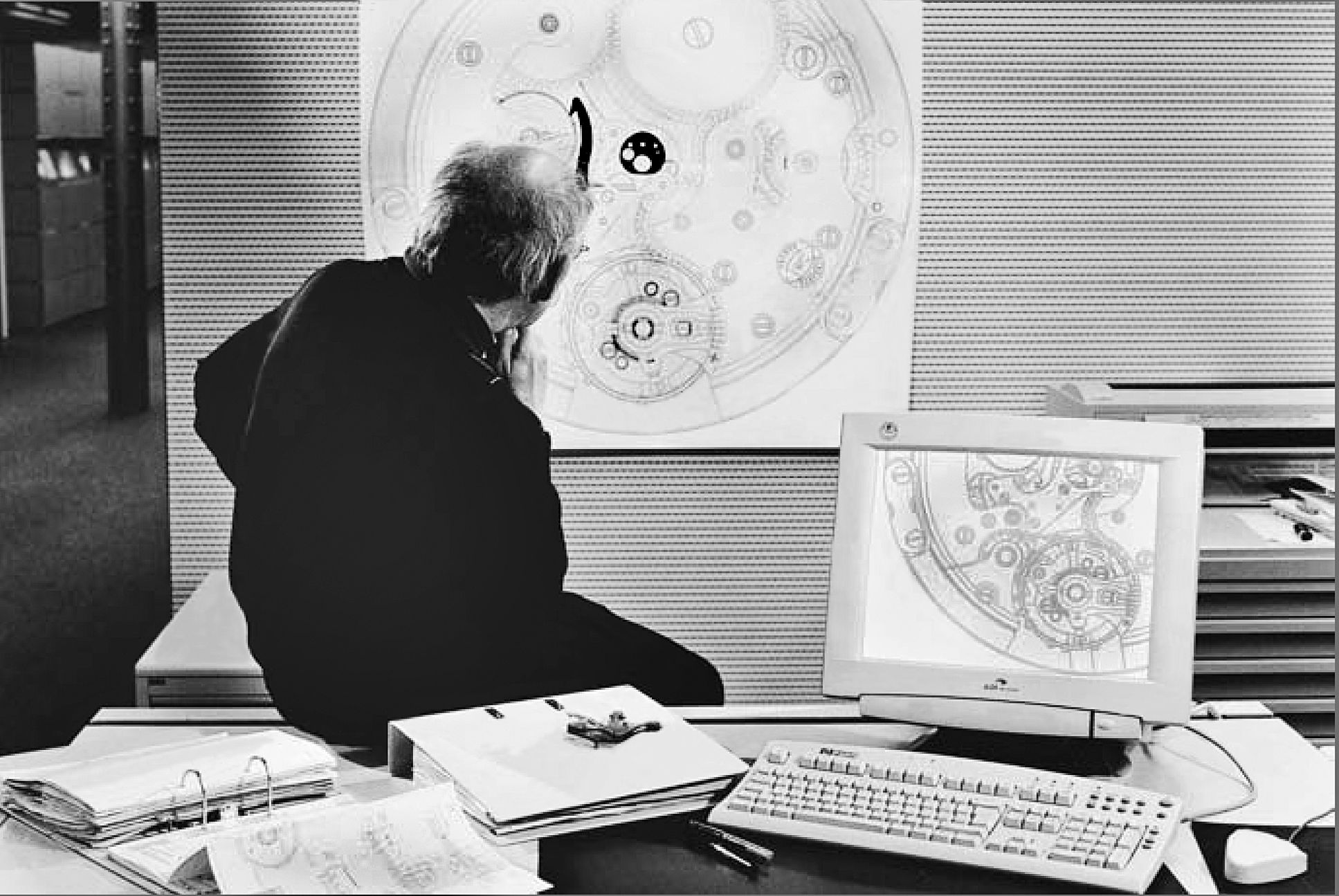

The first Portofino, with complications designed by Klaus, debuted in 1981: the model was the basis for the current series It was not only the design of the watch movement that was new; it was also Klaus’s approach to developing it. He was concerned with more than simply creating a complication; even during the design stage he took into consideration the subsequent manufacturing process. “That was a completely new approach,” says Klaus. “Earlier, designers worked completely separately from production. I am, however, first and foremost a watchmaker, and Albert Pellaton had taught me that a watch must be simple, sturdy, and of a high quality.” Klaus has not only displayed a talent for developing complex mechanisms that are suitable for mass production. He is also extremely open-minded and enthusiastic about modern technological innovations. In the late 1980s, Klaus heard about CAD (computer-aided design programmes) for the first time. “That interested me very much and I absolutely wanted to have something like that,” he says.

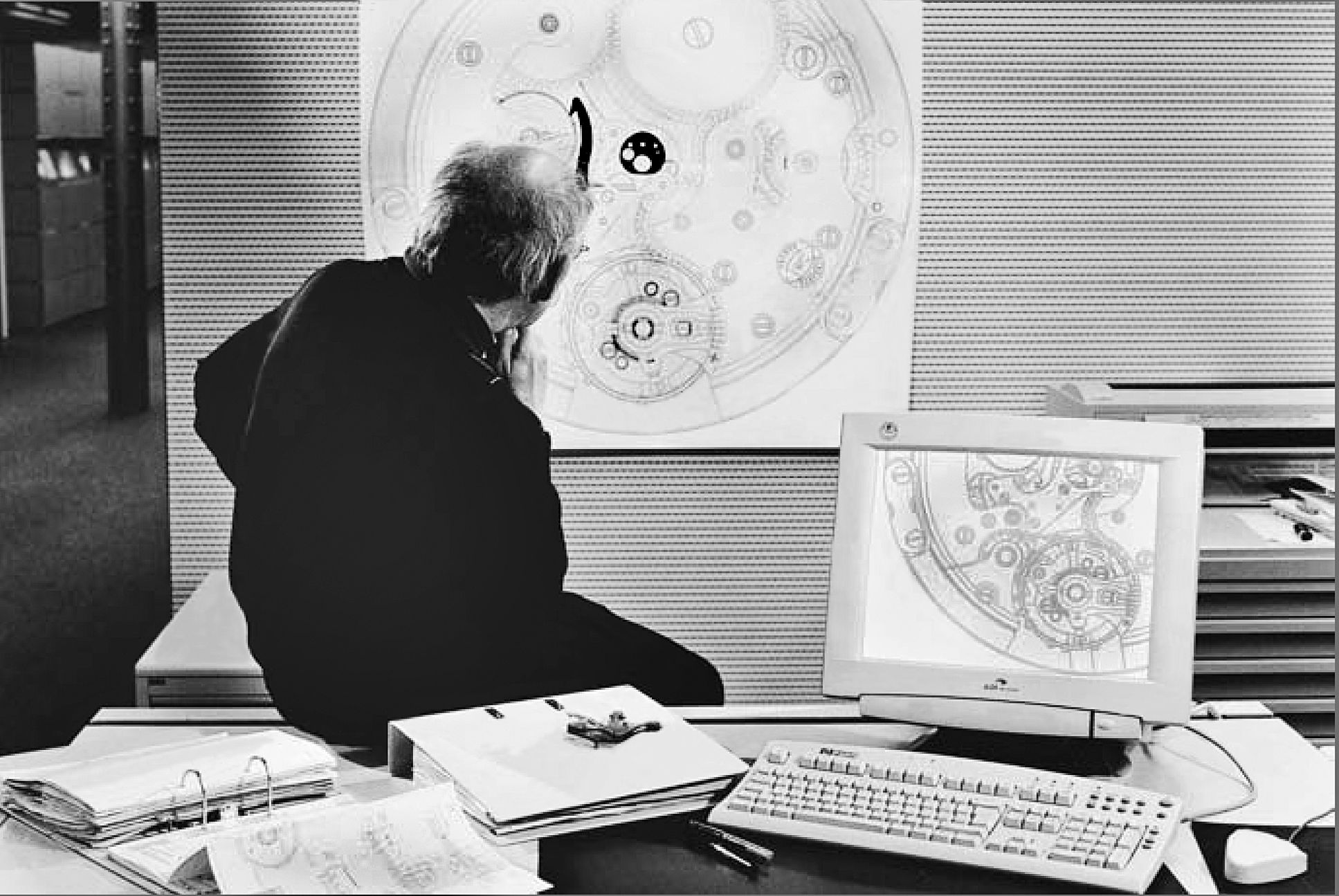

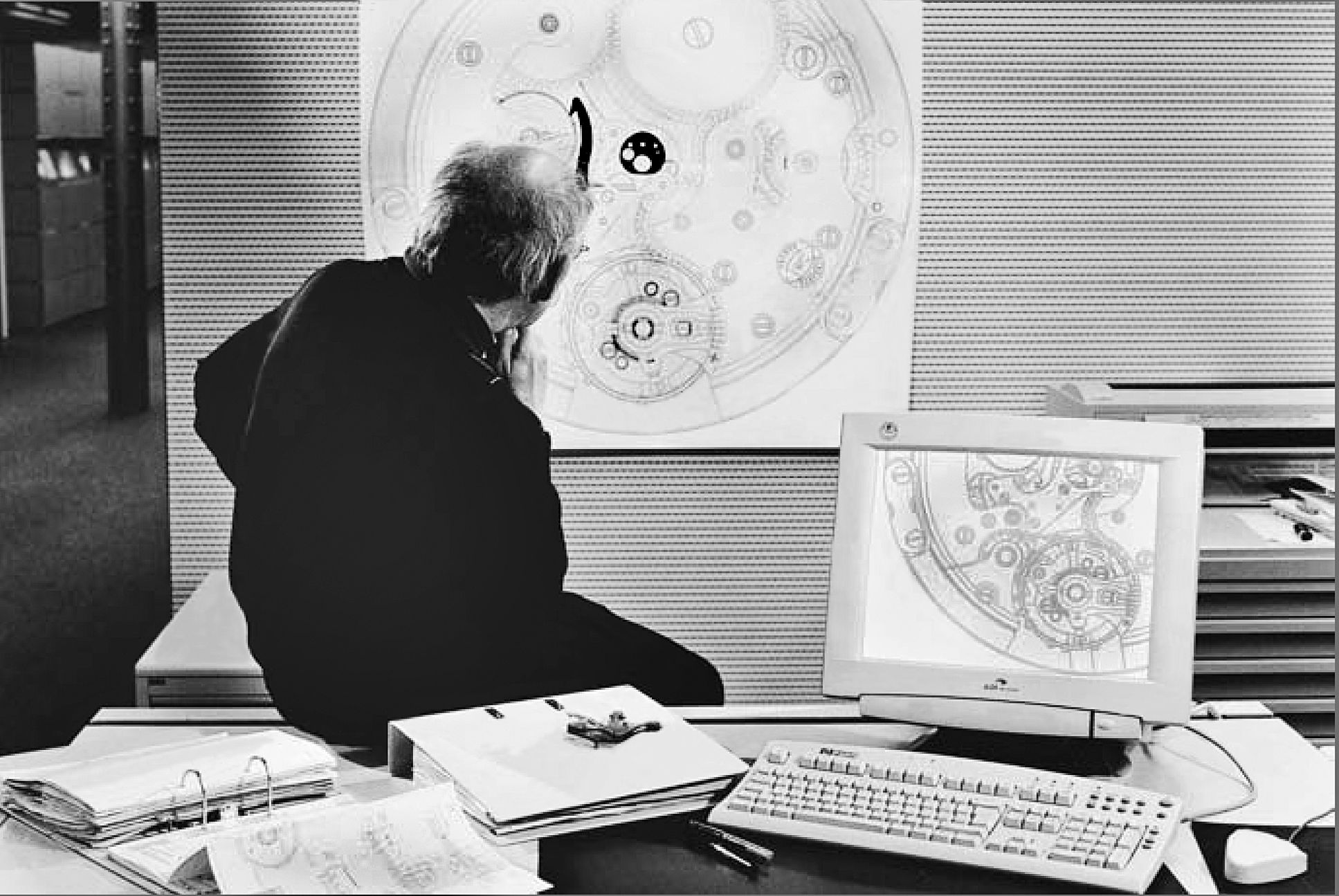

In 1988, Klaus got his first computer, which he describes as “a huge, bulky thing.” After only one week of training, he began to use it for his design work. “From then on, I never picked up my drafting pencils again,” Klaus says. At that point, computer-aided design was relatively simple and still only two-dimensional, but the technology improved over the years and Klaus evolved enthusiastically along with it. The conversion to computerised production opened more new opportunities for him. “I could draw parts any way I pleased,” he says. “And a CNC wire EDM machine would produce those parts exactly as I wanted them to be. This period of development was an exciting adventure.”

Kurt Klaus

Kurt Klaus The adventure did not end for Klaus, even when he gave up many of his day-to-day responsibilities in 1999. He remained involved in IWC’s design department and only gradually withdrew from development work. In recent years, the charming man with the mischievous smile and back bent from so many years at the workbench has become a sought-after international ambassador for IWC. Georges Kern, CEO for the brand, recognises Klaus’s value. “He has garnered worldwide renown for IWC with his extraordinary initiative, great creative power and inventiveness,” Kern says. “Kurt Klaus never promoted himself personally, but he has been an important representative of our company.”

This story first appeared in WatchTime US and was carried in WatchTime India's 2012 July-September edition. The story has been updated with current day figures.