Bienne/Biel is home to more than 100 watch companies. Among them is the biggest watch company in the world, the Swatch Group, whose headquarters overlook Lake Bienne. Bienne is also where the biggest Swiss watch brand, Rolex, makes its movements, in a huge complex of buildings on the outskirts of town. These two hulking giants, the Swatch Group and Rolex, dominate the town’s watch industry, together employing about three-quarters of all its workers.

Several Swatch Group brands are also based here, including Omega, the second- or third-largest Swiss brand (both Omega and Cartier claim the number two spot), Swatch, CK Watch and Tiffany. So are countless contractors who supply components and services for watch brands in Bienne and elsewhere. The Federation Horlogère, or Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry, is headquartered here, as is one of Switzerland’s three COSC chronometre-testing facilities. The watch industry is not Bienne’s biggest business: watches are surpassed by services, healthcare and communications.

The town sits on the eastern edge of the Swiss watchmaking region that runs along the border with France. If you travel north out of Bienne, or Biel-Bienne, as it is known officially (Biel is a German name; Bienne a French one — the town is bilingual by statute), within minutes you’ll be in the Jura Mountains, where watchmaking took root in the 18th century. It was the influx of French-speaking watchmakers from the Jura that turned German-speaking Biel into Biel-Bienne and, ultimately, a watch superpower.

Watchmaking wasn’t Bienne’s first industry. During the early decades of the Industrial Revolution, the town depended on the textile industry, specifically, a dyeing technique called “Indiennes,” in which patterns were printed on cotton fabric. It had been developed in India (hence the name) and then, in the 18th century, adopted by fabric makers in Europe. An Indiennes factory opened in Bienne in 1747. By 1800, one-third of the population, or more than 1,000 people, worked in the Indiennes industry.

Hans Stockli was Bienne's mayor for 20 years

Hans Stockli was Bienne's mayor for 20 yearsTrouble hit 40 years later, when synthetic dyes rendered the complicated Indienne dyeing process obsolete. The industry shut down. Bienne suffered.

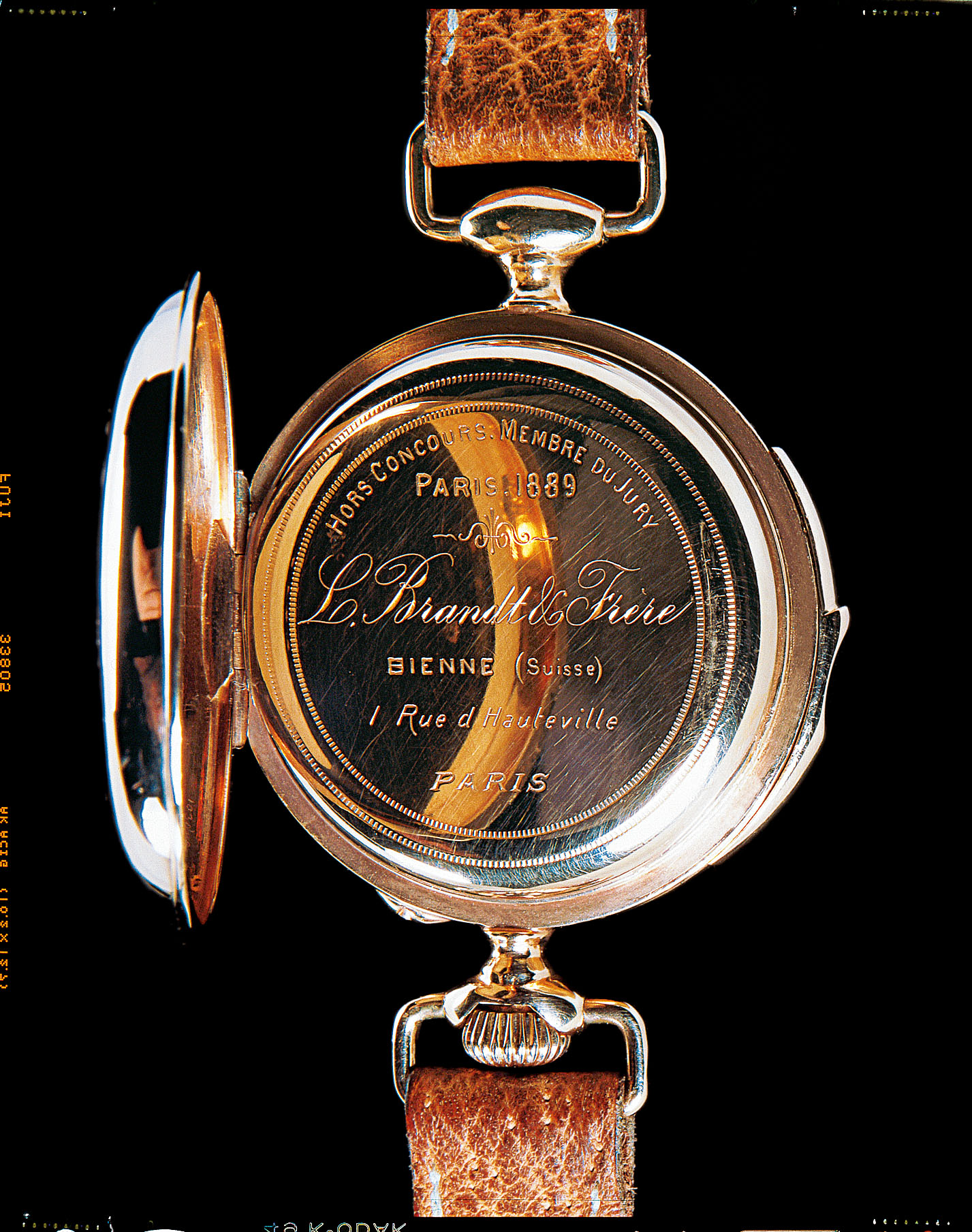

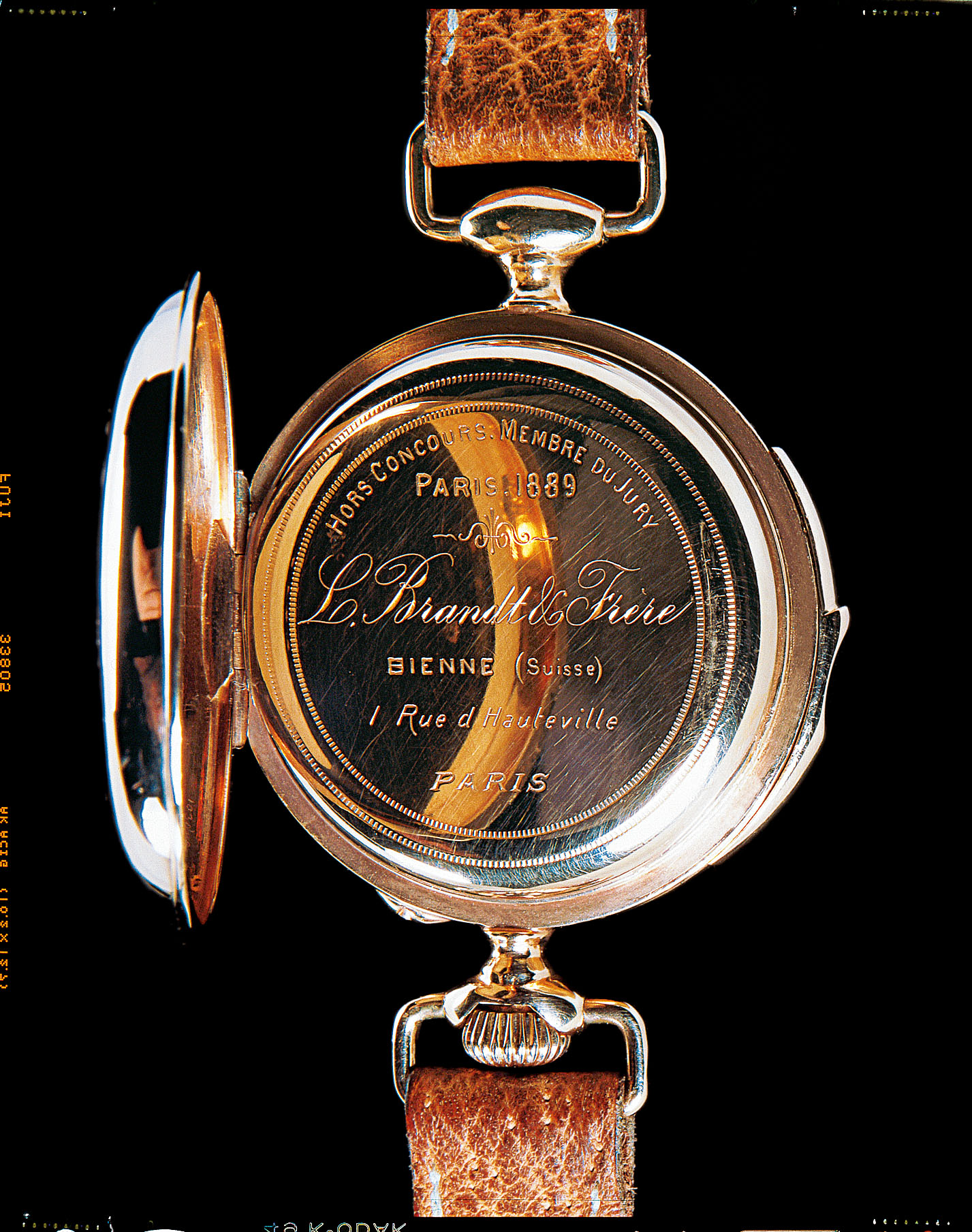

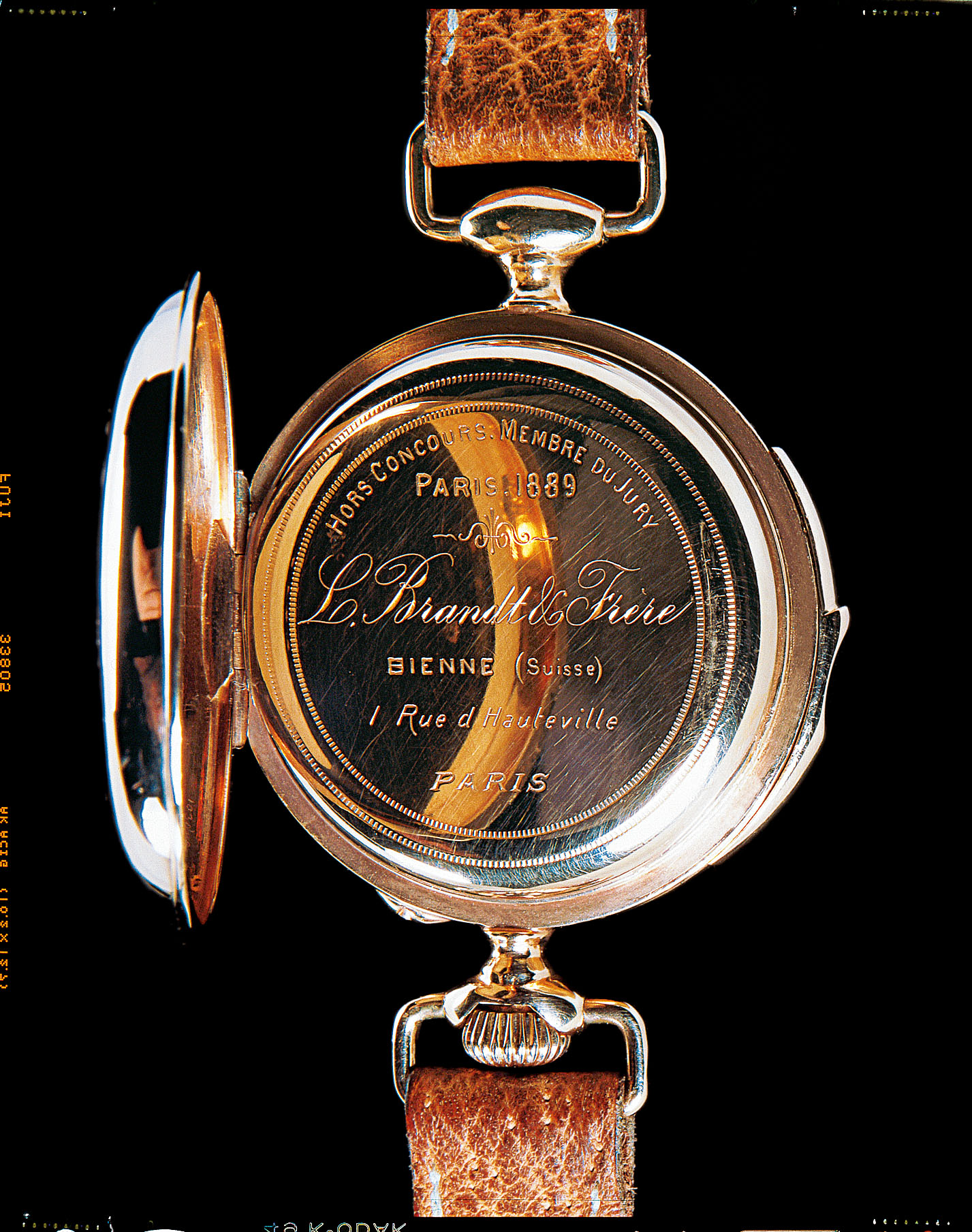

A minute-repeater wristwatch by Louis Brandt & Frere, now known as Omega

A minute-repeater wristwatch by Louis Brandt & Frere, now known as OmegaThen, to the rescue, came a political refugee named Ernst Schüler, born in the German town of Darmstadt. He moved to Bienne in 1833 and, a decade later, as a member of the municipal council, sought ways to employ workers who had lost their textile jobs. In 1844, he pushed through a proposal that the town grant a three-year tax exemption to all watchmakers who moved to Bienne to open businesses there. The Jura’s floodgates opened, as the first group of tax-haven seekers pulled in other watchmakers long after the tax holiday was over. By 1860, Bienne had more than 800 watchmakers. Bienne’s watch industry snowballed. By 1900, Bienne’s population of 29,557 included 3,400 watchmakers.

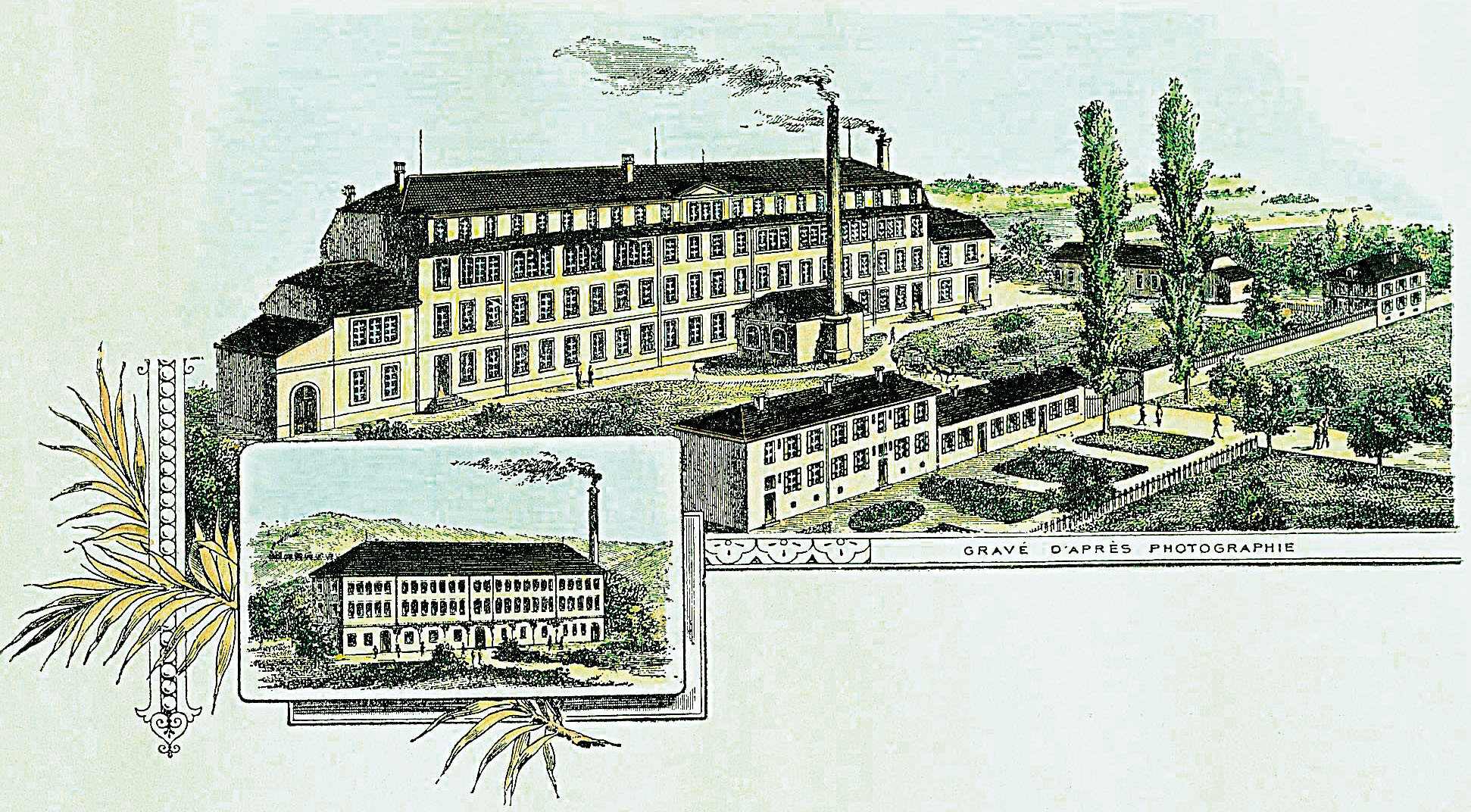

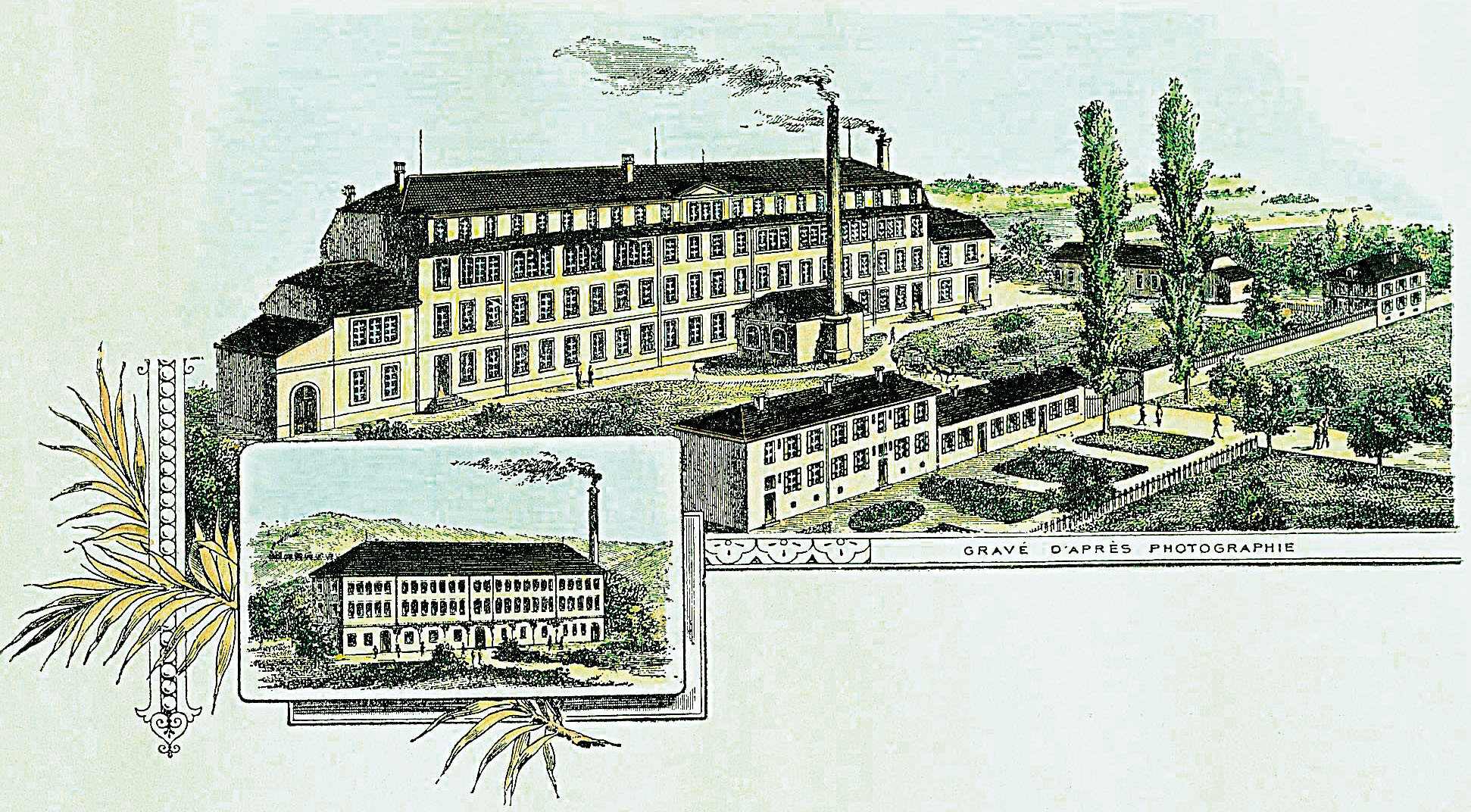

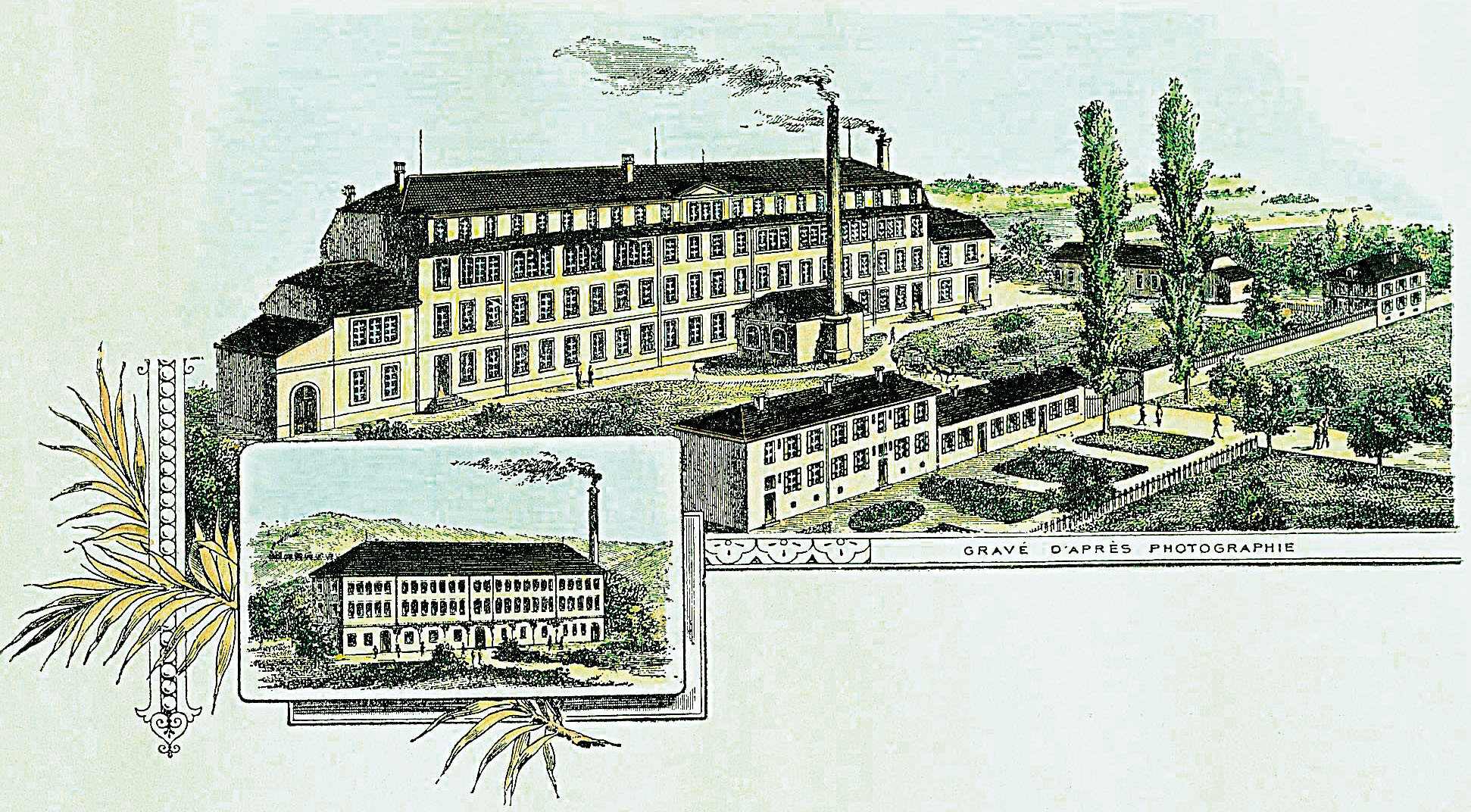

The Louis Brandt & Frere factory in the Gurzelen section of Bienne

The Louis Brandt & Frere factory in the Gurzelen section of BienneAmong the immigrants were two brothers, Louis-Paul and César Brandt. In 1848, their father, Louis Brandt, had founded the company that would be known as Omega. He had done so not in Bienne, but in the watchmaking town of La Chaux-de-Fonds, high up in the Jura, where he died in 1879. The next year, Louis-Paul and César moved to Bienne. They were drawn there because they wanted to set up a modern, automated factory. But La Chaux-de-Fonds, like the rest of Canton Neuchâtel, resisted the new mass-production methods emerging in watchmaking and other industries. So the brothers left for Bienne, in Canton Berne, and there bought a former cotton mill in the section of town known as Gurzelen, east of the city centre. By 1889, their company, Louis Brandt et Frère, was Switzerland’s biggest watch factory, employing 400 people and making 1,00,000 watches per year. Today, Omega is still located in Gurzelen, next to the Suze (Schüss in German) River that cuts through the town.

The Aegler-Rolex movement-making factory as it looked in 1995

The Aegler-Rolex movement-making factory as it looked in 1995Edouard Heuer, founder of what is now TAG Heuer, also made the move from La Chaux-de-Fonds to Bienne, arriving there in the 1860s. The company remained in the town until the 1980s, when the TAG Group (Techniques d’Avant Garde) bought Heuer and moved it to Marin, next to Neuchâtel.

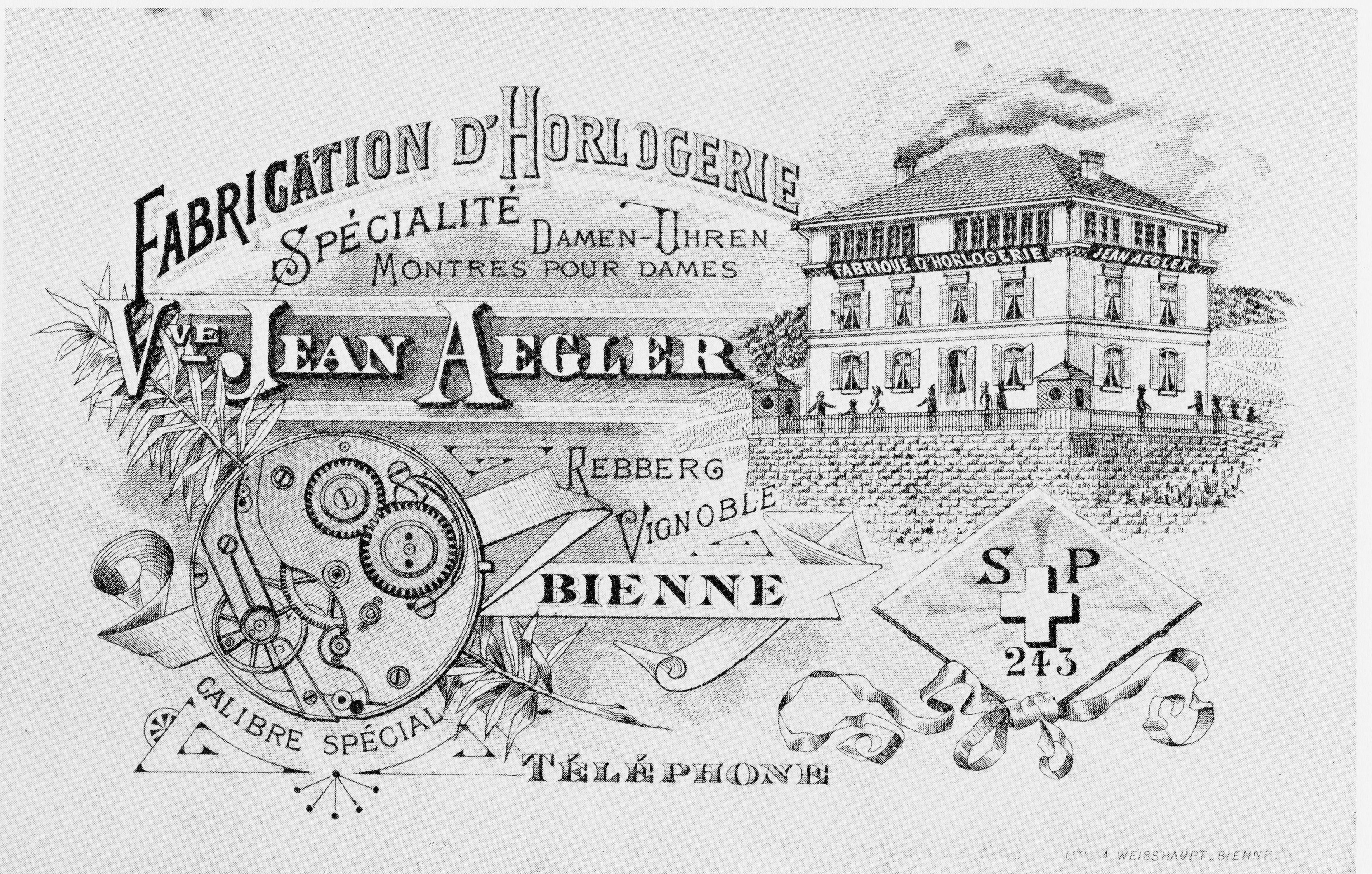

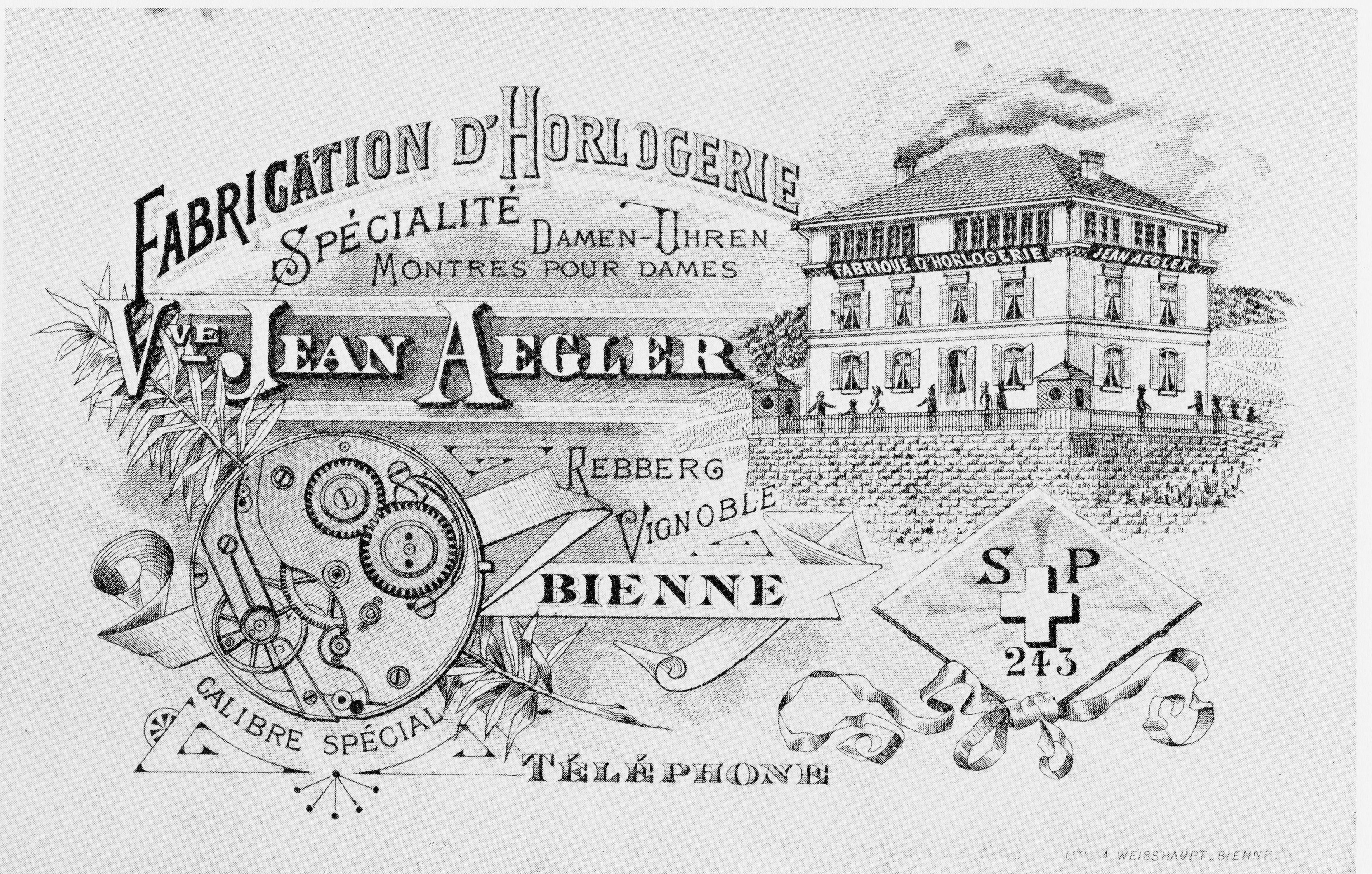

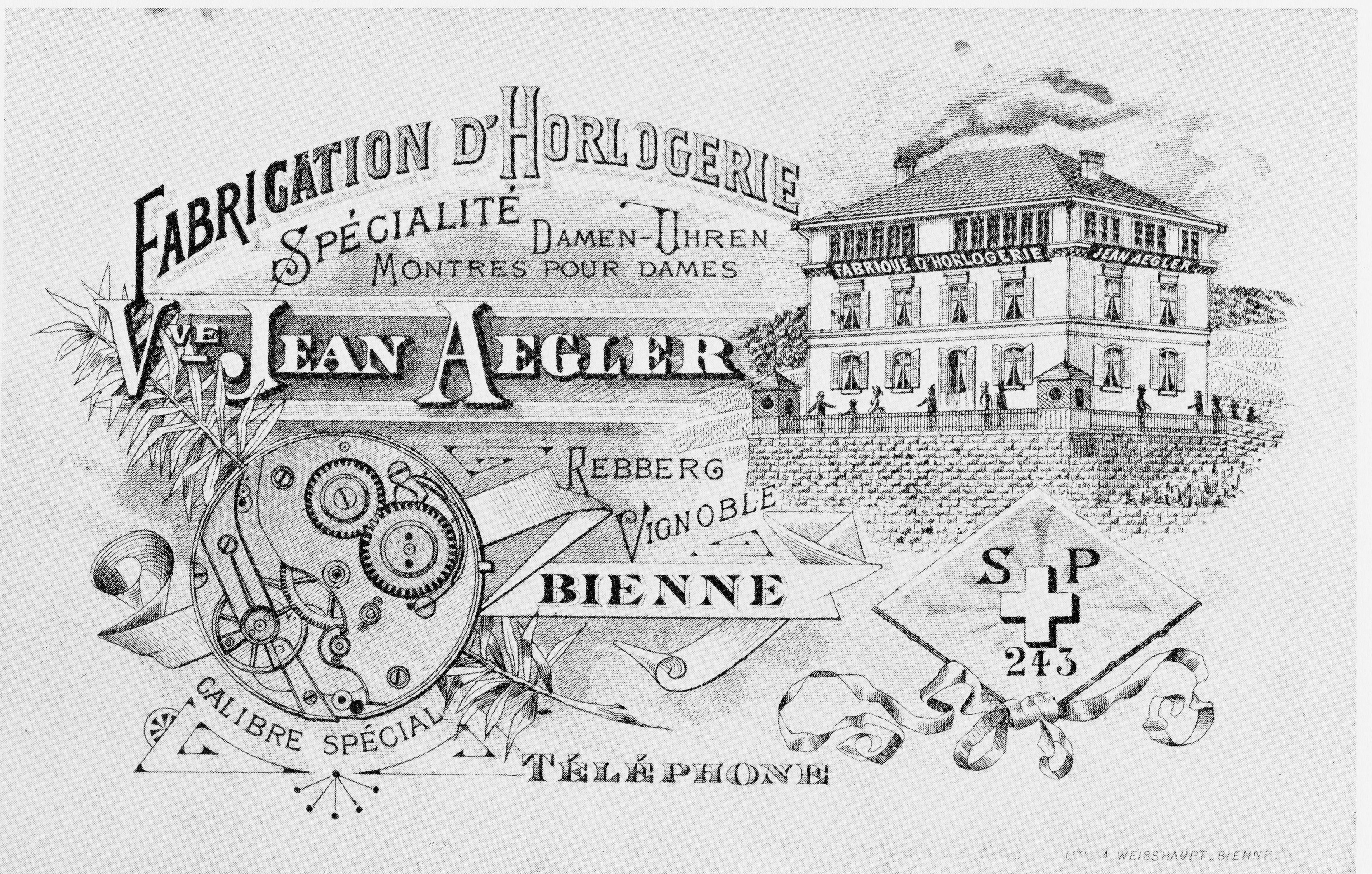

A 1900 Aegler advertisement. Courtesy of the Neuhaus museum

A 1900 Aegler advertisement. Courtesy of the Neuhaus museumOne spur to Bienne’s industrial growth during the 19th century was its supply of hydroelectric power. Its source was the Taubenloch gorge, a mile-long ravine that concentrates the waters of the Suze into a rushing torrent as they make their way down the Saint-Imier Valley to Lake Bienne. The Taubenloch, recently reopened after repairs were made to enhance its safety, is popular with hikers. At first, watch companies bought power from a wire-making plant called the Tréfileries de Boujean (Boujean is a section of Bienne) but they were soon setting up their own turbines.

A Neuhaus museum exhibit showing a Bienne watchmaker, circa 1870-1880

A Neuhaus museum exhibit showing a Bienne watchmaker, circa 1870-1880Today, Bienne visitors interested in the town’s industrial history can learn much at the Neuhaus museum, on the Promenade de la Suze near Bienne’s Old Town. (The Old Town, though short on watch-industry connections, is charming, with its 15th-century Saint Benoit church and quaint fountains. Its cobblestone square, called “The Ring,” was once a venue for public executions.) The Neuhaus is housed in a former Indiennes factory named François Verdan & Cie, which was in business from 1784 to 1842.

At the museum you can see a detailed chronicle of Bienne’s watch history through the industry’s many ups and downs. There is a wide range of watches from Bienne companies, including two showcases of vintage Rolexes and, oddly, to modern eyes, itsy-bitsy women’s watches from Bienne-based Glycine, now a proponent of watch gigantism. The museum also has old film clips, including one of the Omega factory in 1920, and another, rather poignant one from 1972, offering a Cassandra-like warning that the Swiss industry must adopt new production methods in the face of competition from Japan and the United States.

Bienne is bilingual by law: all signs must be in German and French

Bienne is bilingual by law: all signs must be in German and FrenchAt the same time that the Brandt brothers were setting up their modern factory, another Bienne watch power was being born. In 1878, Jean and Marie Aegler set up a factory in Bienne that would, a quarter-century later, become Rolex’s movement supplier. It started out making small, high-precision movements for women’s watches. The factory, at Haute-Route 82, was perched above the town in a prominent spot that had once been a vineyard. It is still there, visible from many vantage points in the town. In 1891, after Jean Aegler’s death, the couple’s son Hermann took the reins at the company.

In 1905, a young, German-born, London-based watch entrepreneur named Hans Wilsdorf, an early believer in the commercial potential of the wristwatch, placed a large order with Aegler for the small, wristwatch-sized movements in which Aegler’s company specialised. It was the start of a fruitful marriage. Aegler became the sole supplier of movements to Wilsdorf, whose watches, starting in 1908, were sold under the name “Rolex.” In 1919, Wilsdorf moved his headquarters to Geneva, where he would make his cases, assemble his watches and market them throughout the world. Writing in his memoirs, he explained, with more candour than tact, “We wanted to leave to our factory in Bienne [i.e., Aegler’s factory] exclusively the production of watch movements, while we ourselves would create in Geneva case models adapted to the refined tastes of the Genevans.”

Bienne watchmaker Armin Strom at work in his atelier

Bienne watchmaker Armin Strom at work in his atelierRefined tastes or no, Bienne’s watch industry hummed along through the late 19th and early 20th century. Brands popped up: Recta, in 1898; Concord, in 1908; Glycine, 1914; Mido, 1918; Milus, 1919, along with many now gone.

Rolex's gigantic movement-making facility on the outskirts of Bienne

Rolex's gigantic movement-making facility on the outskirts of BienneThe Great Depression hit Bienne especially hard. Watchmaking was the town’s biggest industry by far, and as a luxury-goods business, it struggled more than many. During the Depression’s worst years, one-third of Bienne’s watch-factory workers were either unemployed or working part-time.

The headquarters of the H5 Group, whose brands include Perrelet

The headquarters of the H5 Group, whose brands include PerreletIn response to the economic debacle, Bienne made its first major effort to diversify into another industry. It lured General Motors with a five-year-long tax break, and in 1935 the company opened a factory in town, next to the train station so that it would have easy access to the train tracks. GM stayed in Bienne until 1975.

The years after World War II were nearly as kind to Bienne as the Depression had been cruel. Omega went great guns. By the 1950s, it was the most famous watch brand in the world. During the 1960s, it turned out one million watches per year and employed 2,300 people. And it wasn’t just Omega that was breathing new life into Bienne. In 1960, the American company Bulova Corp. introduced its extremely successful Accutron watch, which it manufactured in a factory at Faubourg du Jura 44 (the building, which, incidentally, was one of the first fully air-conditioned buildings in Switzerland, now houses the Candino brand, owned by the Festina Group). The watch, fitted with an innovative electronic movement regulated by a tuning fork—a precursor to the quartz watch—was the most popular luxury watch of its time.

Swatch Group headquarter

Swatch Group headquarter

In 1964, Bienne’s population reached its all-time peak of 64,848. That year, the town voted to make Champs de Boujean, an area to the east of the city, where Rolex is now located, into an industrial zone to alleviate crowding in the town proper. It was the continuation of a trend: factories had been opening on the periphery of the town since a few years after World War II.

The post-war salad days ended with another economic calamity, this one particular to Bienne and other Swiss watch cities. It was the quartz crisis, when the entire Swiss watch industry was blindsided by the swift triumph of quartz watches over mechanical ones. The trouble started with the Japanese company Seiko’s launch of the first quartz watch, in 1969, and continued through the 1970s and into the 1980s. Swiss companies, slow to accept the new technology, and hobbled by currency exchange rates that gave Japanese watches an advantage over Swiss ones, scrambled to keep up with the Japanese and US quartz-watch industries, but could not.

During that time, the number of watch companies in Bienne shrank from 112 (in 1966) to 30. Watchmaking ceded its spot as the top employer in Bienne to machine making. Between 1967 and 1987, the number of people working in the watch industry shrank from 6,350 to 1,700. Other businesses that relied on the watch industry also suffered. Bienne lost 10,000 industrial jobs during the crisis. The Swiss writer Benedikt Loderer describes Bienne at that time as a “gray, sad, poor and depressed town.”

Bienne came back from the brink for two reasons. First was the now-famous rescue of the Swiss watch industry by Swiss banks in the early 1980s, and the consolidation of the Swiss watch industry that followed. The turnaround began in 1981, when Swiss banks, seeing that the country’s beloved and economically indispensable watch industry was collapsing, began pouring money into it. By the end of 1983, they had pumped in 650 million Swiss francs (about $340 million at the exchange rates of the time) into the two dilapidated, money-losing watch groups: ASUAG, whose chief brand was Longines, and SSIH, whose main brand was Omega.

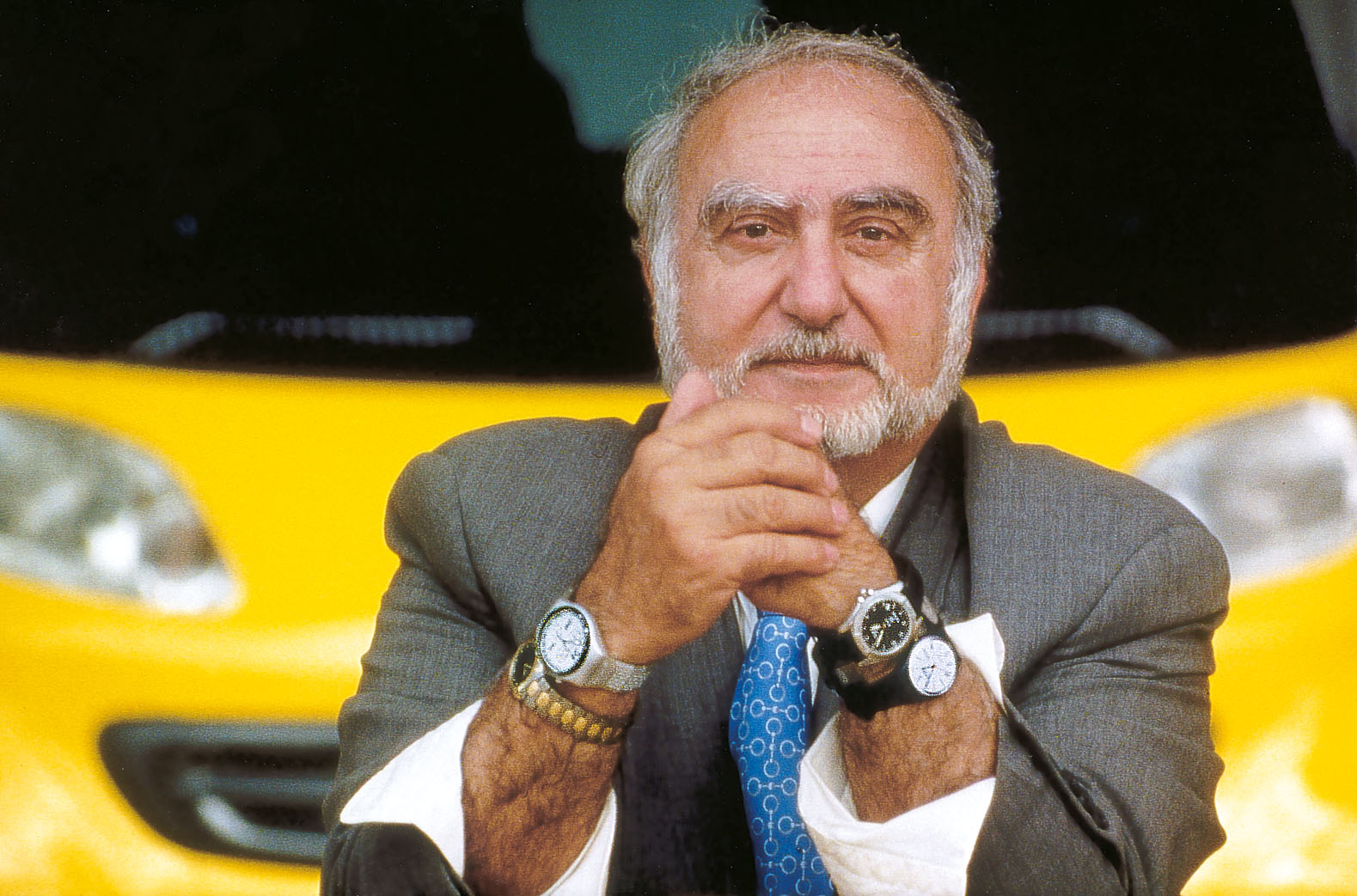

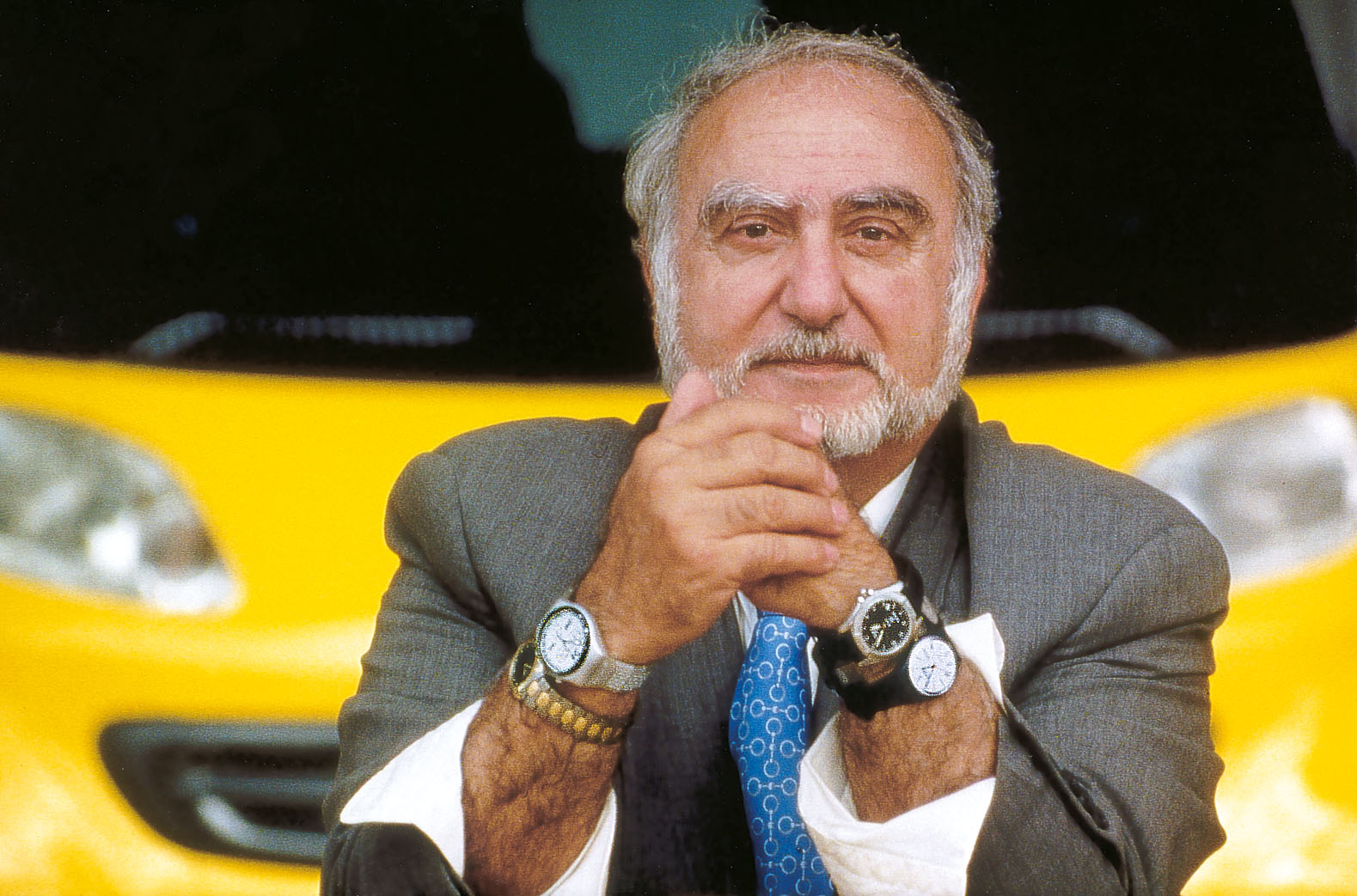

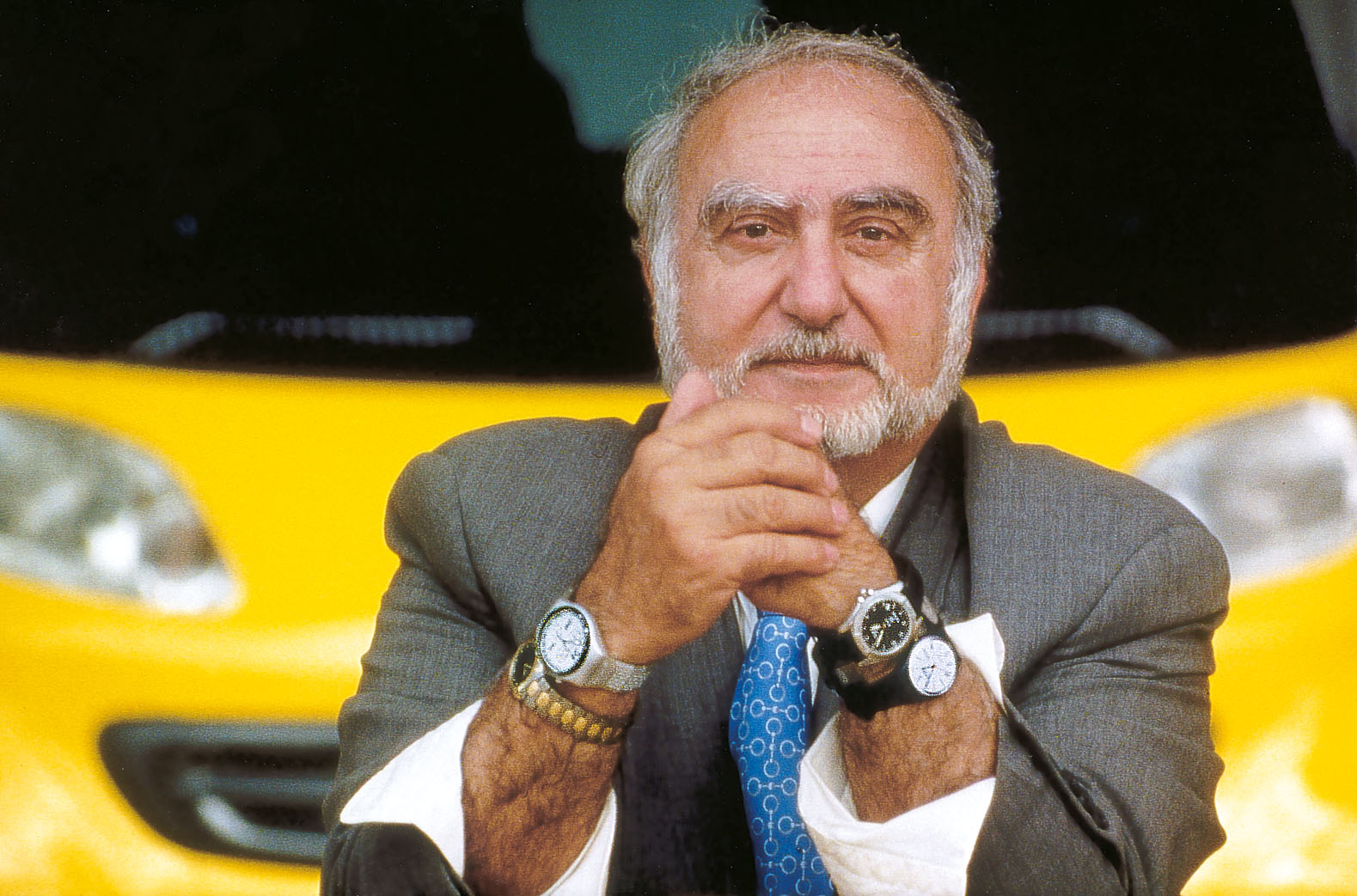

Then, seeing that the industry would have to be restructured to save it, the banks turned to a well-known business consultant based in Zurich. His name is now a household word in all of Switzerland: Nicolas G. Hayek. In 1985, he engineered the merger of ASUAG and SSIH into a single, streamlined company called SMH (Swiss Corp. for Microelectronics and Watchmaking Industries Ltd.) and became its chairman. That company is now called the Swatch Group. Hayek died in June 2010 at the age of 82. His daughter, Nayla Hayek, succeeded him as Swatch Group chairperson. His son, Nick Hayek, Jr., has held the CEO position since 2003.

There was another hero in the rescue: a young, Bienne-born engineer named Ernst Thomke. Before the ASUAG-SSIH merger, Thomke had consolidated the movement factories in ASUAG into a single movement company. That new company took the name of one of the ASUAG movement makers: ETA, which became part of SMH. ETA’s biggest victory during the rescue era was the Swatch watch, launched in 1983. Books and myriad scholarly papers have been written about Swatch and its role both in reviving the Swiss watch industry and in revolutionising watch marketing. (Thomke remained at ETA until 1991.)

Swatch Group founder Nicolas Hayek was an honorary citizen of Bienne, one of just three in the town's history

Swatch Group founder Nicolas Hayek was an honorary citizen of Bienne, one of just three in the town's historyThe second factor in Bienne’s watch revival came at the end of the 1980s. Unforeseen by all but a few prescient individuals, it is now something every watch fan takes for granted: the revival of the mechanical watch. That revival gave renewed luster to Rolex, which had continued to make mechanical watches through the onslaught of quartz technology. It gave new life to Omega, and either brought into being or restored the fortunes of several other Swatch Group brands: Breguet, Blancpain, Jaquet Droz and Glashütte Original. It ensured that ETA, which was and still is a part of the Swatch Group (ETA is based in nearby Grenchen) became the powerhouse it is today, its strength based largely on its ubiquitous mechanical movements, including the 7750, 2824 and 2892. And it brought to Bienne, as it did to other Swiss towns, an array of mechanical or mostly mechanical brands, some new, some resurrected from the pre-quartz era, along with all the components makers and other suppliers who sell to them. In Bienne (or in its immediate vicinity), these brands include Armin Strom, Doxa, Eberhard, Perrelet, and others.

Now, a generation after the first rays of sunshine appeared in the bleak quartz-crisis sky, Bienne is bustling. Follow Bienne’s main road northeast from the centre of town to the industrial area of Champs de Boujean for a look at one of its major new watch projects: the expansion of Rolex’s already gigantic movement-making plant (or take the public bus and get off at the stop named, simply, “Rolex”). The plant employs about 2,000 people, making it Bienne’s biggest watch-company employer by far. It turns out all the 7,50,000-plus movements used by the Rolex brand each year (the Rolex-owned Tudor brand uses ETA movements).

Rolex moved some of its operations out here in 1994, and now has four adjacent buildings, very imposing-looking and very modern. When the most recent, called Rolex VI, was completed in 2003, the remaining employees still working at the old facility overlooking the Old Town were transferred here. (The old building is right next to the one in which Jean and Marie Aegler founded their movement company in the 19th century.) The old Rolex facility still proudly bears at its top a large sign with the Rolex name flanked by two crown symbols and is one of Bienne’s most familiar landmarks.

The Taubenloch gorge, which provided power for Bienne's watch factories, is a tourist attraction today

The Taubenloch gorge, which provided power for Bienne's watch factories, is a tourist attraction todayThis story was first published in WatchTime US, and then carried in WatchTime India's July–September 2012 issue. We have edited out some information that is no longer relevant.